As more people across the world connect on Facebook, we want to make sure our apps and services work well in a variety of scenarios. At Facebook’s scale, this means testing hundreds of important interactions across numerous types of devices and operating systems for both correctness and speed before we ship new code.

Last year, we introduced the Facebook mobile device lab, which lets engineers run tests by accessing thousands of mobile devices available in our data centers. Since then, we’ve built a new, unified resource management system, codenamed One World, to host these devices and other runtimes such as web browsers and emulators. Engineers at Facebook can use a single API to communicate with these remote resources within their tests and other automated systems. One World has grown to manage tens of thousands of resources and is used to execute more than 1 million jobs each day. At this scale, we have learned a lot, as we encountered unique challenges building a system that can deal with the complexities of device reliability while exposing an easy-to-use API.

Architecture

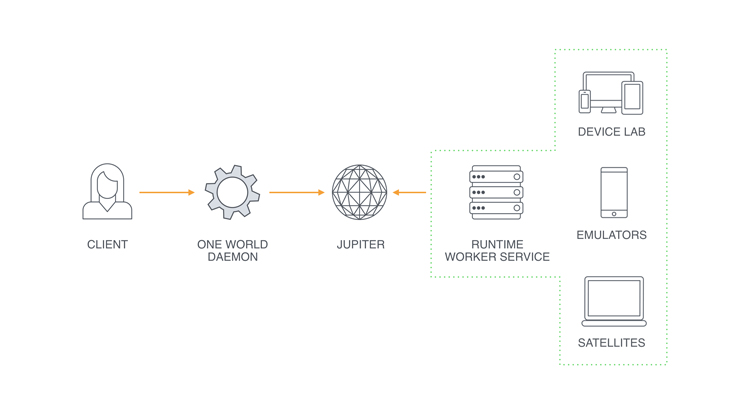

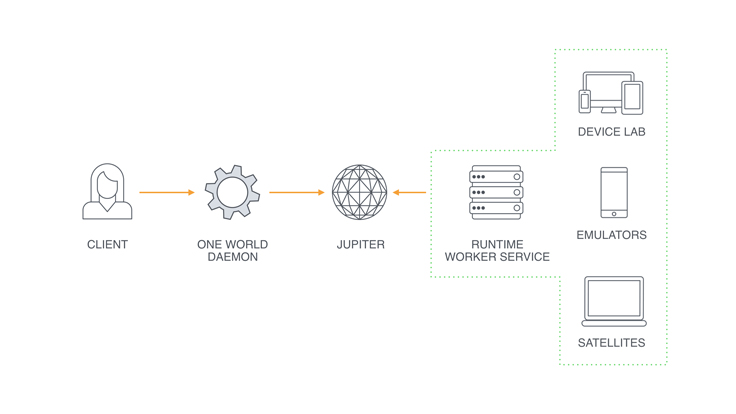

In One World, we aim to support any application that an engineer might want to use with a remote runtime and minimal modifications to their code or environment. This means supporting standard communication mechanisms like adb (Android Debug Bridge) and providing the illusion that remote devices are connected locally. Our system consists of four main components:

- Runtime worker service: Each resource type has its own runtime worker service that runs on machines managing the resource. The worker service manages the life cycle of the resource and responds to requests from clients to use its resources.

- One World daemon: This lightweight service runs on machines that will connect to remote resources. The service implements the protocol to communicate with workers and sets up the environment to allow local processes to communicate with remote resources.

- Scheduler: We use Jupiter, a job-scheduling service at Facebook, to match clients with workers whose available resources match their specified requirements.

- Satellite: This minimal deployment of the worker service allows engineers to connect local resources to the global One World deployment.

Runtime worker service

Each resource hosted in One World has a worker service with the following responsibilities:

- Resource configuration and setup: Before receiving a job, most resources require some sort of initial setup. For mobile devices, this may include unlocking the device, disabling the lock screen, and configuring other system settings. For browsers, it may include starting a selenium stand-alone server to allow it to be controlled remotely.

- Health checks: Physical devices fail after prolonged use, and devices in our labs receive much more use than the average personal device. Worker services have a series of checks that they run to make sure devices are in a healthy state before allowing a client to access them. Some health checks may require technicians to repair or remove the device, and others may be resolved in an automated fashion such as charging a device due to a low battery.

- Restoring state: After a resource has been used, we need to prepare it for the next client. For resources such as emulators, simulators, and browsers, this can be a trivial process like rebooting from an image. Mobile devices present some unique challenges, as a complete reimage is time intensive and adds wear to internal flash storage. To restore to a known good state, worker services will take actions such as rebooting a device to reset most kernel settings, uninstalling applications, and wiping data partitions.

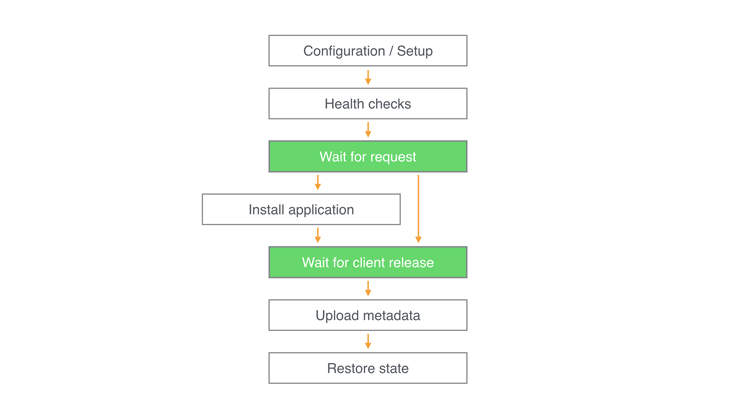

Within the worker service, these steps are expressed as a state machine. Each state has monitoring and logging so we can understand bottlenecks in the system and failure rates by step. An example state machine might take the following form:

In this state machine example, the green steps indicate points where the worker interacts with the client. Tasks like configuration/setup and health checks can occur before a client even connects to a worker. These steps can take several minutes, so running them in advance allows for minimal latency when a client connects — often, our connection latency is as low as just a couple of seconds. Workers can take actions in response to the client request before handing the resource over for use. For example, if a resource is in a distant data center, installing applications on a device may be much faster if run locally on the host machine rather than over the network. After a client disconnects, the worker can attach additional metadata to the session that can be queried later. We use this to store logs (e.g., device logcat) and videos of sessions. By allowing the worker to add metadata asynchronously, the client does not have to wait for uploads to finish.

Worker services are written in Python 3, which lets us run them on a variety of platforms including Linux, Mac OS, and Windows. A separate instance of the service is started for each managed resource. We attempt to isolate these service instances from each other on platforms that support it. On Linux, for example, this means launching each service in its own control group that has been configured to provide access only to the resource it controls.

Remote access to mobile test devices

On Android, we want to support the full set of existing tools on One World, meaning that normal calls to adb must work within our system. Otherwise, every tool used at Facebook would need to be modified to be aware of One World, which would quickly spin out of control. One World runs adb servers on device hosts and provides the illusion of a local adb instance by establishing TCP tunnels. For example, we can create a TCP tunnel on port 5037, the standard adb port, and forward all traffic to the device host’s adb instance. To support adb forward/reverse, we deploy a thin wrapper around the adb binary, which understands these commands and creates tunnels with two hops — first to the device host, then to the device itself.

While the Android development environment has adb for interacting with an Android emulator or device, much of the tooling for iOS development is part of Xcode. As OneWorld runs iOS runtimes remotely, we needed a similar mechanism for remote interactions so that those runtimes could be used for running applications and different kinds of tests.

In 2015, we open-sourced FBSimulatorControl, a project for controlling iOS simulators. We have since extended this project to allow for interfacing with devices, allowing us to accommodate many of the applications that we have at Facebook. Features of FBSimulatorControl include:

- Structured output for automation: FBSimulatorControl reports on the status of devices and simulators in a machine-readable format suitable for interactions such as booting simulators and launching applications.

- Application management: The most common automation scenarios on iOS include the installation and launching of our iOS applications. FBSimulatorControl provides a consistent interface for this across simulators and devices, removing the complexity from the One World worker service.

- Automation of the user interface: iOS engineers may be familiar with the XCUITest framework for writing automated UI tests. At Facebook, we’ve built on top of this framework in our WebDriverAgent project, a WebDriver server that runs on iOS. This allows us to automate the user interface of our iOS applications from another machine without running additional software on the worker. Our end-to-end tests apply this to execute on a separate machine from runtime hosts, bringing big performance wins for test runtimes when parallelized.

- Remote invocation: When reviewing the results of automated tests, additional diagnostic data can be useful. FBSimulatorControl provides APIs for collecting videos and logs from iOS simulators and devices that can then be accessed by clients.

One World daemon

Rather than talk directly to the worker service, clients instead connect to a local daemon that handles the negotiation and environment setup. In this protocol, a client begins by creating a new session with the daemon. The session contains a specification of the type of runtime the client requires and the number of concurrent runtimes it needs. For example, when running a large test suite, a client may request a session for 20 concurrent Android emulators. The daemon prepares the requested resources by reserving a worker service instance and performing runtime-specific preparation steps. For Android sessions, this means setting up the appropriate TCP tunnels to listen on localhost and proxy the traffic to the adb daemon on the remote machine.

As the client requires access to each reserved resource within its session, it will request a “lease” from the daemon. The daemon will respond with connection details or inform the client if the resource is not yet available. These connection details include information like the local ports to use for adb and FBSimulatorControl. After a client has finished using the resource, it releases it by calling in to the daemon again. At this point, the daemon then either frees the resource entirely to be used by a different client, or retains it to be reused within the same session if possible.

Throughout the session, the workers and daemon communicate as part of the aforementioned state machine model. Once a worker becomes reserved through the scheduling service, it connects to the corresponding daemon to service the job. During the session, the daemon and worker will perform liveness checks, as either of them might die unexpectedly. Once the client has completed its session, the daemon sends a message to the worker to advance to the “restore state” part of its state machine.

Satellite mode

While having access to managed remote resources allows clients to scale, sometimes engineers want to use the same tools on local devices to debug an issue. We offer a “satellite service” that allows engineers to connect a local resource to the One World cloud. This means the phone on your desk can be shared with any other engineer and used by all of Facebook’s automation by just running a simple command. Like the worker services, the satellite service establishes a series of SSH tunnels from a local machine to One World to connect to the rest of the infrastructure. Targeting a satellite device instead of a managed device requires no code changes, and the satellite service sets up all required networking paths and publishes the resource’s availability.

Using One World

The One World daemon described above takes care of the heavy lifting of connecting to the service. We provide simple libraries to handle common patterns of communication with the daemon to enable engineers to easily integrate with One World. The code snippet below demonstrates the Python API for running an adb command on a One World device. It starts the One World daemon, and then OneWorldADB establishes a session and blocks until a device is available. A Python context manager takes care of tearing everything down once the engineer’s code has finished.

with OneWorldDaemon() as daemon, OneWorldADB(

daemon,

consumer='demo',

capabilities={'device-group': 'nexus-6'},

) as adb:

adb.run('logcat')

Using multiple concurrent resources is also supported. The One World daemon manages these concurrent resources and, via the API, engineers implement their own system-specific functionality. In the example below, 10 emulators are used to run 100 jobs — the next job will be run as soon as a new emulator becomes available. The results variable at the end will contain 100 results returned by the run_custom_test method.

with OneWorldAndroidADB(daemon, num_emulators=10) as android:

futures = [

asyncio.ensure_future(

android.run_with_emulator(run_custom_test)

) for _ in range(100)

]

results = await asyncio.gather(*futures)

Ad hoc usage is supported through the CLI:

Applications

Beyond providing an environment for the ad hoc use of resources, One World supports numerous infrastructure projects at Facebook, including:

- End-to-end and integration testing: On every code change to our apps, we run a large suite of tests to avoid introducing new bugs in our codebase. At Facebook’s scale, thousands of code changes are made each day, resulting in hundreds of thousands of test runs. One World allows us to run these tests on emulators, simulators, and devices at this scale and provides quick feedback on results as engineers write code.

- CT-Scan: Beyond finding bugs, we also carefully test our apps for performance regressions to make sure our apps run smoothly on a large variety of devices. One World provides access to the devices representative of those owned by people who use Facebook, and it allows CT-Scan to focus on testing performance rather than managing devices.

- Sapienz: A multi-objective end-to-end testing system, Sapienz automatically generates test sequences using search-based software engineering to find crashes using the shortest path it can find. The Sapienz team can focus on the crash-finding algorithms while letting One World manage the emulators it uses.

We have many important applications for One World today, but we expect our future work to greatly expand how we use One World in our engineering workflow. We’re working on some exciting new features, including:

- Live streaming: Engineers often want to reproduce bugs that are platform-specific. Sometimes having just a remote interface like adb isn’t enough — you may want to scroll through News Feed, write comments, or tap the Like button. We’re building a live streaming service that will allow engineers to interact with devices in our lab from within a web browser. This means they will be able to debug an issue on an obscure model of phone at the click of a button, all while sitting at their desk.

- Remote profiling: The same code can have very different performance on different devices due to varying OS versions, hardware differences, and more. We’re working on building a service that allows engineers to submit code and retrieve detailed profiler data across many devices simultaneously to understand how these factors impact their code’s performance.