Displaying images quickly and efficiently on Facebook for Android is important. Yet we have had many problems storing images effectively over the years. Images are large, but devices are small. Each pixel takes up 4 bytes of data — one for each of red, green, blue, and alpha. If a phone has a screen size of 480 x 800 pixels, a single full-screen image will take up 1.5 MB of memory. Phones often have very little memory, and Android devices divide up what memory they have among multiple apps. On some devices, the Facebook app is given as little as 16 MB — and just one image could take up a tenth of that!

What happens when your app runs out of memory? It crashes. We set out to solve this by creating a library we’re calling Fresco — it manages images and the memory they use. Crashes begone.

Regions of memory

To understand what Facebook did here, we need to understand the different heaps of memory available on Android.

The Java heap is the one subject to the strict, per-application limits set by the device manufacturer. All objects created using the Java language’s new operator go here. This is a relatively safe area of memory to use. Memory is garbage-collected, so when the app has finished with memory, the system will automatically reclaim it.

Unfortunately, this process of garbage collection is precisely the problem. To do more than basic reclamations of memory, Android must halt the application completely while it carries out the garbage collection. This is one of the most common causes of an app appearing to freeze or stall briefly while you are using it. It’s frustrating for people using the app, and they may try to scroll or press a button — only to see the app wait inexplicably before responding.

In contrast, the native heap is the one used by the C++ new operator. There is much more memory available here. The app is limited only by the physical memory available on the device. There is no garbage collection and nothing to slow things down. However, C++ programs are responsible for freeing every byte of memory they allocate, or they will leak memory and eventually crash.

Android has another region of memory, called ashmem. This operates much like the native heap, but has additional system calls. Android can “unpin” the memory rather than freeing it. This is a lazy free; the memory is freed only if the system actually needs more memory. When Android “pins” the memory back, old data will still be there if it hasn’t been freed.

Purgeable bitmaps

Ashmem is not directly accessible to Java applications, but there are a few exceptions, and images are one of them. When you create a decoded (uncompressed) image, known as a bitmap, the Android API allows you to specify that the image be purgeable:

BitmapFactory.Options = new BitmapFactory.Options();

options.inPurgeable = true;

Bitmap bitmap = BitmapFactory.decodeByteArray(jpeg, 0, jpeg.length, options);

Purgeable bitmaps live in ashmem. However, the garbage collector does not automatically reclaim them. Android’s system libraries “pin” the memory when the draw system is rendering the image, and “unpin” it when it’s finished. Memory that is unpinned can be reclaimed by the system at any time. If an unpinned image ever needs to be drawn again, the system will just decode it again, on the fly.

This might seem like a perfect solution, but the problem is that the on-the-fly decode happens on the UI thread. Decoding is a CPU-intensive operation, and the UI will stall while it is being carried out. For this reason, Google now advises against using the feature. They now recommend using a different flag, inBitmap. However, this flag did not exist until Android 3.0. Even then, it was not useful unless most of the images in the app were the same size, which definitely isn’t the case for Facebook. It was not until Android 4.4 that this limitation was removed. However, we needed a solution that would work for everyone using Facebook, including those running Android 2.3.

Having our cake and eating it too

We found a solution that allows us to have the best of both worlds — both a fast UI and fast memory. If we pinned the memory in advance, off the UI thread, and made sure it was never unpinned, then we could keep the images in ashmem but not suffer the UI stalls. As luck would have it, the Android Native Development Kit (NDK) has a function that does precisely this, called AndroidBitmap_lockPixels. The function was originally intended to be followed by a call to unlockPixels to unpin the memory again.

Our breakthrough came when we realized we didn’t have to do that. If we called lockPixels without a matching unlockPixels, we created an image that lived safely off the Java heap and yet never slowed down the UI thread. A few lines of C++ code, and we were home free.

Write code in Java, but think like C++

As we learned from Spider-Man, “With great power comes great responsibility.” Pinned purgeable bitmaps have neither the garbage collector’s nor ashmem’s built-in purging facility to protect them from memory leaks. We are truly on our own.

In C++, the usual solution is to build smart pointer classes that implement reference counting. These make use of C++ language facilities — copy constructors, assignment operators, and deterministic destructors. This syntactic sugar does not exist in Java, where the garbage collector is assumed to be able to take care of everything. So we have to somehow find a way to implement C++-style guarantees in Java.

We made use of two classes to do this. One is simply called SharedReference. This has two methods, addReference and deleteReference, which callers must call whenever they take the underlying object or let it out of scope. Once the reference count goes to zero, resource disposal (such as Bitmap.recycle) takes place.

Yet, obviously, it would be highly error-prone to require Java developers to call these methods. Java was chosen as a language to avoid doing this! So on top of SharedReference, we built CloseableReference. This implements not only the Java Closeable interface, but Cloneable as well. The constructor and the clone() method call addReference(), and the close() method calls deleteReference(). So Java developers need only follow two simple rules:

- On assigning a CloseableReference to a new object, call

.clone(). - Before going out of scope, call

.close(), usually in a finally block.

These rules have been effective in preventing memory leaks, and have let us enjoy native memory management in large Java applications like Facebook for Android and Messenger for Android.

It’s more than a loader — it’s a pipeline

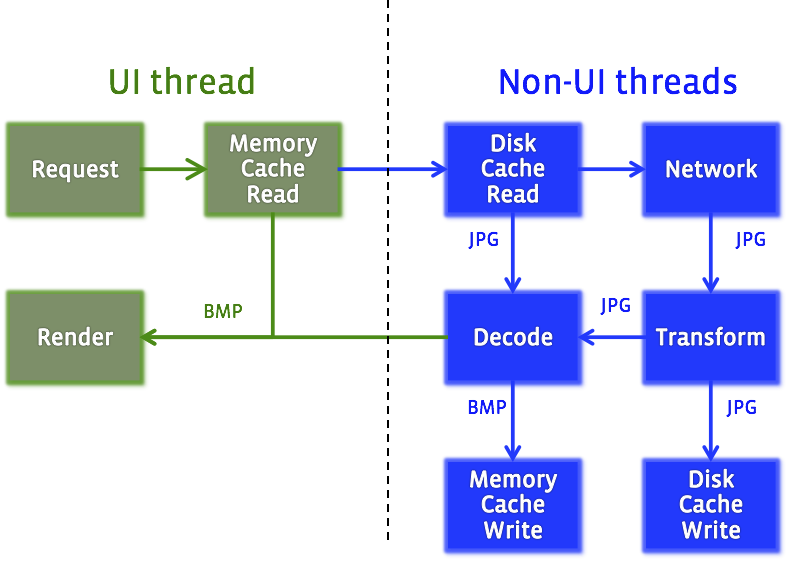

There are many steps involved in showing an image on a mobile device:

Several excellent open source libraries exist that perform these sequences — Picasso, Universal Image Loader, Glide, and Volley, to name a few. All of these have made important contributions to Android development. We believe our new library goes further in several important ways.

Thinking of the steps as a pipeline rather than as a loader in itself makes a difference. Each step should be as independent of the others as possible, taking an input and some parameters and producing an output. It should be possible to do some operations in parallel, others in serial. Some execute only in specific conditions. Several have particular requirements as to which threads they execute on. Moreover, the entire picture becomes more complex when we consider progressive images. Many people use Facebook over very slow Internet connections. We want these users to be able to see their images as quickly as possible, often even before the image has actually finished downloading.

Stop worrying, love streaming

Asynchronous code on Java has traditionally been executed through mechanisms like Future. Code is submitted for execution on another thread, and an object like a Future can be checked to see if the result is ready. This, however, assumes that there is only one result. When dealing with progressive images, we want there to be an entire series of continuous results.

Our solution was a more generalized version of Future, called DataSource. This offers a subscribe method, to which callers must pass a DataSubscriber and an Executor. The DataSubscriber receives notifications from the DataSource on both intermediate and final results, and offers a simple way to distinguish between them. Because we are so often dealing with objects that require an explicit close call, DataSource itself is a Closeable.

Behind the scenes, each of the boxes above is implemented using a new framework, called Producer/Consumer. Here we drew inspiration from ReactiveX frameworks. Our system has interfaces similar to RxJava, but more appropriate for mobile and with built-in support for Closeables.

The interfaces are kept simple. Producer has a single method, produceResults, which takes a Consumer object. Consumer, in turn, has an onNewResult method.

We use a system like this to chain producers together. Suppose we have a producer whose job is to transform type I to type O. It would look like this:

public class OutputProducer<I, O> implements Producer<O> {

private final Producer<I> mInputProducer;

public OutputProducer(Producer<I> inputProducer) {

this.mInputProducer = inputProducer;

}

public void produceResults(Consumer<O> outputConsumer, ProducerContext context) {

Consumer<I> inputConsumer = new InputConsumer(outputConsumer);

mInputProducer.produceResults(inputConsumer, context);

}

private static class InputConsumer implements Consumer<I> {

private final Consumer<O> mOutputConsumer;

public InputConsumer(Consumer<O> outputConsumer) {

mOutputConsumer = outputConsumer;

}

public void onNewResult(I newResult, boolean isLast) {

O output = doActualWork(newResult);

mOutputConsumer.onNewResult(output, isLast);

}

}

}

This lets us chain together a very complex series of steps and still keep them logically independent.

Animations — from one to many

Stickers, which are animations stored in the GIF and WebP formats, are well liked by people who use Facebook. Supporting them poses new challenges. An animation is not one bitmap but a whole series of them, each of which must be decoded, stored in memory, and displayed. Storing every single frame in memory is not tenable for large animations.

We built AnimatedDrawable, a Drawable capable of rendering animations, and two backends for it — one for GIF, the other for WebP. AnimatedDrawable implements the standard Android Animatable interface, so callers can start and stop the animation whenever they want. To optimize memory usage, we cache all the frames in memory if they are small enough, but if they are too large for that, we decode on the fly. This behavior is fully tunable by the caller.

Both backends are implemented in C++ code. We keep a copy of both the encoded data and parsed metadata, such as width and height. We reference count the data, which allows multiple Drawables on the Java side to access a single WebP image simultaneously.

How do I love thee? Let me Drawee the ways . . .

When images are being downloaded from the network, we want to show a placeholder. If they fail to download, we show an error indicator. When the image does arrive, we do a quick fade-in animation. Often we scale the image, or even apply a display matrix, to render it at a desired size using hardware acceleration. And we don’t always scale around the center of the image — the useful focus point may well be elsewhere. Sometimes we want to show the image with rounded corners, or even as a circle. All of these operations need to be fast and smooth.

Our previous implementation involved using Android View objects — swapping out a placeholder View for an ImageView when the time came. This turned out to be quite slow. Changing Views forces Android to execute an entire layout pass, definitely not something you want to happen while users are scrolling. A more sensible approach would be to use Android’s Drawables, which can be swapped out on the fly.

So we built Drawee. This is an MVC-like framework for the display of images. The model is called DraweeHierarchy. It is implemented as a hierarchy of Drawables, each of which applies a specific function — imaging, layering, fade-in, or scaling — to the underlying image.

DraweeControllers connect to the image pipeline — or to any image loader — and take care of backend image manipulation. They receive events back from the pipeline and decide how to handle them. They control what the DraweeHierarchy actually displays — whether a placeholder, error condition, or finished image.

DraweeViews have only limited functionality, but what they provide is decisive. They listen for Android system events that signal that the view is no longer being shown on-screen. When going off-screen, the DraweeView can tell the DraweeController to close the resources used by the image. This avoids memory leaks. In addition, the controller will tell the image pipeline to cancel the network request, if it hasn’t gone out yet. Thus, scrolling through a long list of images, as Facebook often does, will not break the network bank.

With these facilities, the hard work of displaying images is gone. Calling code need only instantiate a DraweeView, specify a URI, and, optionally, name some other parameters. Everything else happens automatically. Developers don’t need to worry about managing image memory or streaming the updates to the image. Everything is done for them by the libraries.

Fresco

Having built this elaborate tool set for image display and manipulation, we wanted to share it with the Android developer community. We are pleased to announce that, as of today, this project is now available as open source.

A fresco is a painting technique that has been popular around the world for centuries. With this name, we honor the many great artists who have used this form, from Italian Renaissance masters like Raphael to the Sigiriya artists of Sri Lanka. We don’t pretend to be on that level. We do hope that Android app developers enjoy using our library as much as we’ve enjoyed building it.