Facebook for iOS (FBiOS) is the oldest mobile codebase at Meta. Since the app was rewritten in 2012, it has been worked on by thousands of engineers and shipped to billions of users, and it can support hundreds of engineers iterating on it at a time.

After years of iteration, the Facebook codebase does not resemble a typical iOS codebase:

- It’s full of C++, Objective-C(++), and Swift.

- It has dozens of dynamically loaded libraries (dylibs), and so many classes that they can’t be loaded into Xcode at once.

- There is almost zero raw usage of Apple’s SDK — everything has been wrapped or replaced by an in-house abstraction.

- The app makes heavy use of code generation, spurred by Buck, our custom build system.

- Without heavy caching from our build system, engineers would have to spend an entire workday waiting for the app to build.

FBiOS was never intentionally architected this way. The app’s codebase reflects 10 years of evolution, spurred by technical decisions necessary to support the growing number of engineers working on the app, its stability, and, above all, the user experience.

Now, to celebrate the codebase’s 10-year anniversary, we’re shedding some light on the technical decisions behind this evolution, as well as their historical context.

2014: Establishing our own mobile frameworks

Two years after Meta launched the native rewrite of the Facebook app, News Feed’s codebase began to have reliability issues. At the time, News Feed’s data models were backed by Apple’s default framework for managing data models: Core Data. Objects in Core Data are mutable, and that did not lend itself well to News Feed’s multithreaded architecture. To make matters worse, News Feed utilized bidirectional data flow, stemming from its use of Apple’s de facto design pattern for Cocoa apps: Model View Controller.

Ultimately, this design exacerbated the creation of nondeterministic code that was very difficult to debug or reproduce bugs. It was clear that this architecture was not sustainable and it was time to rethink it.

While considering new designs, one engineer investigated React, Facebook’s (open source) UI framework, which was becoming quite popular in the Javascript community. React’s declarative design abstracted away the tricky imperative code that caused issues in Feed (on web), and leveraged a one-way data flow, which made the code much easier to reason about. These characteristics seemed well suited for the problems News Feed was facing. There was only one problem.

There was no declarative UI in Apple’s SDK.

Swift wouldn’t be announced for a few months, and SwiftUI (Apple’s declarative UI framework) wouldn’t be announced until 2019. If News Feed wanted to have a declarative UI, the team would have to build a new UI framework.

Ultimately, that’s what they did.

After spending a few months building and migrating News Feed to run on a new declarative UI and a new data model, FBiOS saw a 50 percent performance improvement. A few months later, they open-sourced their React-inspired UI framework for mobile, ComponentKit.

To this day, ComponentKit is still the de facto choice for building native UIs in Facebook. It has provided countless performance improvements to the app via view reuse pools, view flattening, and background layout computation. It also inspired its Android counterpart, Litho, and SwiftUI.

Ultimately, the choice to replace the UI and data layer with custom infra was a trade-off. To achieve a delightful user experience that could be reliably maintained, new employees would have to shelve their industry knowledge of Apple APIs to learn the custom in-house infra.

This wouldn’t be the last time FBiOS would have to make a decision that balanced end user experience with developer experience and speed. Going into 2015, the app’s success would trigger what we refer to as a feature explosion. And that presented its own set of unique challenges.

2015: An architectural inflection point

By 2015, Meta had doubled down on its “Mobile First” mantra, and the FBiOS codebase saw a meteoric rise in the number of daily contributors. As more and more products were integrated into the app, its launch time began to degrade, and people began to notice. Toward the end of 2015, startup performance was so slow (nearly 30 seconds!) that it risked being killed by the phone’s OS.

Upon investigation, it was clear that there were many contributing factors to degraded startup performance. For the sake of brevity, we’ll focus only on the ones that had a long-term effect on the app’s architecture:

- The app’s ‘pre-main’ time was growing at an unbounded rate, as the app’s size grew with each product.

- The app’s ‘module’ system gave each product ungoverned access to all the app’s resourcing. This led to a tragedy of the commons issue as each product leveraged its ‘hook’ into startup to perform computationally expensive operations so that initial navigation to that product would be snappy.

The changes that were needed to mitigate and improve startup would fundamentally alter the way product engineers wrote code for FBiOS.

2016: Dylibs and modularity

According to Apple’s wiki about improving launch times, a number of operations have to be performed before an app’s ‘main’ function can be called. Generally, the more code an app has, the longer this will take.

While ‘pre-main’ contributed only a small subset of the 30 seconds being spent during launch, it was a particular concern because it would continue to grow at an unbounded rate as FBiOS continued to amass new features.

To help mitigate the unbounded growth of the app’s launch time, our engineers began to move large swaths of product code into a lazily loaded container known as a dynamic library (dylib). When code is moved into a dynamically loaded library, it isn’t required to load before the app’s main() function.

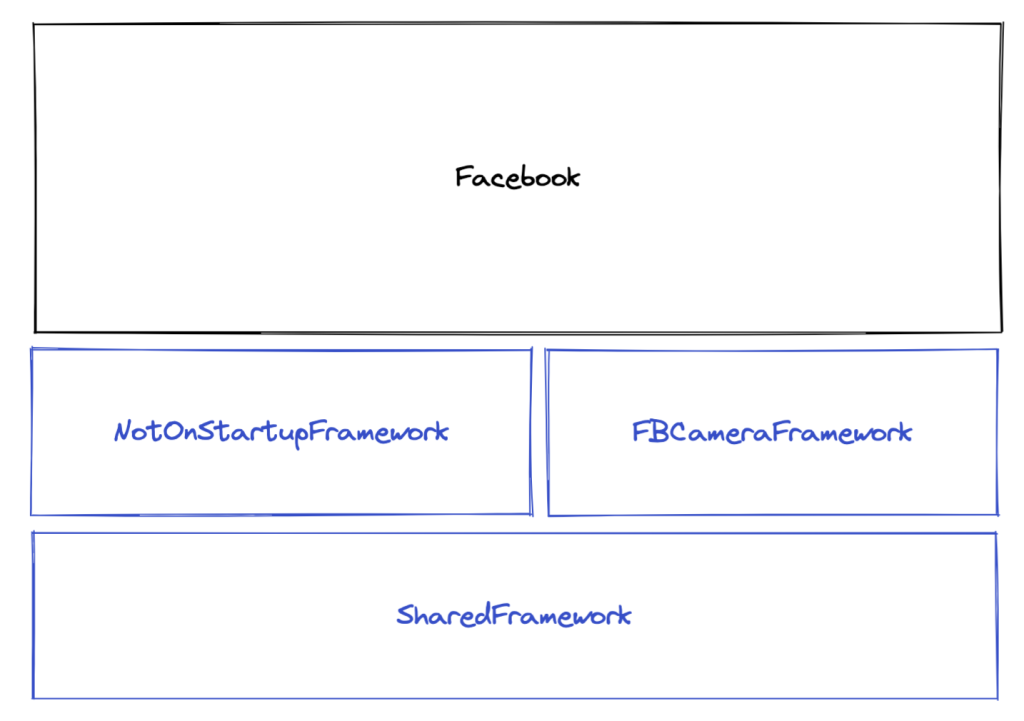

Initially, the FBiOS dylib structure looked like this:

Two product dylibs (FBCamera and NotOnStartup) were created, and a third dylib (FBShared) was used to share code between the various dylibs and the main app’s binary.

The dylib solution worked beautifully. FBiOS was able to curb the unbounded growth of the app’s startup time. As the years went by, most code would end up in a dylib so that startup performance stayed fast and was unaffected by the constant fluctuation of added or removed products in the app.

The addition of dylibs triggered a mental shift in the way Meta’s product engineers wrote code. With the addition of dylibs, runtime APIs like NSClassFromString() risked runtime failures because the required class lived in unloaded dylibs. Since many of the FBiOS core abstractions were built on iterating through all the classes in memory, FBiOS had to rethink how many of its core systems worked.

Aside from the runtime failures, dylibs also introduced a new class of linker errors. In the event the code in Facebook (the startup set) referenced code in a dylib, engineers would see a linker error like this:

Undefined symbols for architecture arm64:

"_OBJC_CLASS_$_SomeClass", referenced from:

objc-class-ref in libFBSomeLibrary-9032370.a(FBSomeFile.mm.o)To fix this, engineers were required to wrap their code with a special function that could load a dylib if necessary:

Suddenly:

int main() {

DoSomething(context);

}

Would look like this:

int main() {

FBCallFunctionInDylib(

NotOnStatupFramework,

DoSomething,

context

);

}

The solution worked, but had quite a few code smells:

- The app-specific dylib enum was hard-coded into various call sites. All apps at Meta had to share a dylib enum, and it was the reader’s responsibility to determine whether that dylib was used by the app the code was running in.

- If the wrong dylib enum was used, the code would fail, but only at runtime. Given the sheer amount of code and features in the app, this late signal led to a lot of frustration during development.

On top of all that, our only system to safeguard against the introduction of these calls during startup was runtime-based, and many releases were delayed while last-minute regressions were introduced into the app.

Ultimately, the dylib optimization curbed the unbounded growth of the app’s launch time, but it signified a massive inflection point in the way the app was architected. FBiOS engineers would spend the next few years re-architecting the app to smooth some of the rough edges introduced by the dylibs, and we (eventually) shipped an app architecture that was more robust than ever before.

2017: Rethinking the FBiOS architecture

With the introduction of dylibs, a few key components of FBiOS had to be rethought:

- The ‘module registration system’ could no longer be runtime-based.

- Engineers needed a way to know whether any codepath during startup could trigger a dylib load.

To address these issues, FBiOS turned to Meta’s open source build system, Buck.

Within Buck, each ‘target’ (app, dylib, library, etc.) is declared with some configuration, like so:

apple_binary(

name = "Facebook",

...

deps = [

":NotOnStartup#shared",

":FBCamera#shared",

],

)

apple_library(

name = "NotOnStartup",

srcs = [

"SomeFile.mm",

],

labels = ["special_label"],

deps = [

":PokesModule",

...

],

)

Each ‘target’ lists all information needed to build it (dependencies, compiler flags, sources, etc.), and when ‘buck build’ is called, it builds all this information into a graph that can be queried.

$ buck query “deps(:Facebook)”

> :NotOnStartup

> :FBCamera

$ buck query “attrfilter(labels, special_label, deps(:Facebook))”

> :NotOnStartupUsing this core concept (and some special sauce), FBiOS began to produce some buck queries that could generate a holistic view of the classes and functions in the app during build. This information would be the building block of the app’s next generation of architecture.

2018: The proliferation of generated code

Now that FBiOS was able to leverage Buck to query for information about code in the dependency, it could create a mapping of “function/classes -> dylibs” that could be generated on the fly.

{

"functions": {

"DoSomething": Dylib.NotOnStartup,

...

},

"classes": {

"FBSomeClass": Dylib.SomeOtherOne

}

}

Using that mapping as input, FBiOS used it to generate code that abstracted away the dylib enum from call sites:

static std::unordered_map<const char *, Dylib> functionToDylib {{

{ "DoSomething", Dylib.NotOnStartup },

{ "FBSomeClass", Dylib.SomeOtherOne },

...

}};

Using code generation was appealing for a few reasons:

- Because the code was regenerated based on local input, there was nothing to check in, and there were no more merge conflicts! Given that the engineering body of FBiOS could double every year, this was a big development efficiency win.

- FBCallFunctionInDylib no-longer required an app-specific dylib (and thus could be renamed to ‘FBCallFunction’). Instead, the call would read from static mapping generated for each application during build.

Combining Buck query with code generation proved to be so successful that FBiOS used it as bedrock for a new plugin system, which eventually replaced the runtime-based app-module system.

Moving signal to the left

With the new Buck-powered plugin system. FBiOS was able to replace most runtime failures with build-time warnings by migrating bits of infra to a plugin-based architecture.

When FBiOS is built, Buck can produce a graph to show the location of all the plugins in the app, like so:

From this vantage point, the plugin system can surface build-time errors for engineers to warn:

- “Plugin D, E could trigger a load of a dylib. This is not allowed, since the caller of these plugins lives in the app’s startup path.”

- “There is no plugin for rendering Profiles found in the app … this means that navigating to that screen will not work.”

- “There are two plugins for rendering Groups (Plugin A, Plugin B). One of them should be removed.”

With the old app module system, these errors would be “lazy” runtime assertions. Now, engineers are confident that when FBiOS is built successfully, it won’t fail because of missing functionality, dylibs loading during app startup, or invariants in the module runtime system.

The cost of code generation

While migrating FBiOS to a plugin system has improved the app’s reliability, provided faster signals to engineers, and made it possible for the app to trivially share code with our other mobile apps, it came at a cost:

- Plugin errors are not on Stack Overflow and can be confusing to debug.

- A plugin system based on code generation and Buck is a far cry from traditional iOS development.

- Plugins introduce a layer of indirection to the codebase. Where most apps would have a registry file with all features, these are generated in FBiOS and can be surprisingly difficult to find.

There is no doubt that plugins led FBiOS farther away from idiomatic iOS development, but the trade-offs seem to be worth it. Our engineers can change code used in many apps at Meta and be sure that if the plugin system is happy, no app should crash because of missing functionality in a rarely tested codepath. Teams like News Feed and Groups can build an extension point for plugins and be sure that product teams can integrate into their surface without touching the core code.

2020: Swift and language architecture

While most of this article has focused on architectural changes stemming from scale issues in the Facebook app, changes in Apple’s SDK have also forced FBiOS to rethink some of its architectural decisions.

In 2020, FBiOS began to see a rise in the number of Swift-only APIs from Apple and a growing sentiment for more Swift in the codebase. It was finally time to reconcile with the fact that Swift was an inevitable tenant in FB apps.

Historically, FBiOS had used C++ as a lever to build abstraction, which saved on code size because of C++’s zero overhead principle. But C++ does not interop with Swift (yet). For most FBiOS APIs (like ComponentKit), some kind of shim would have to be created to use in Swift — creating code bloat.

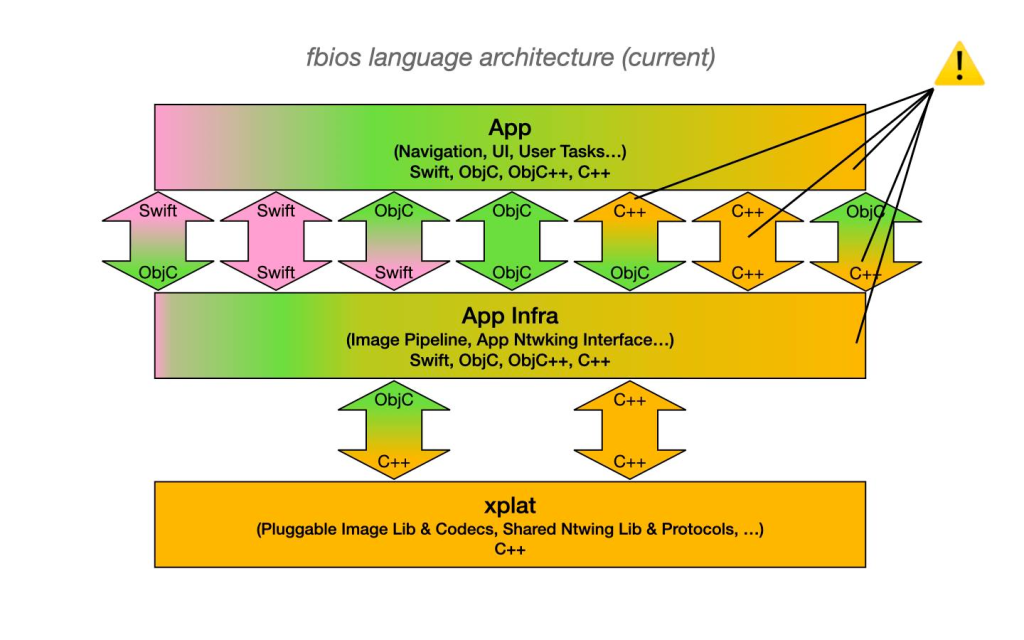

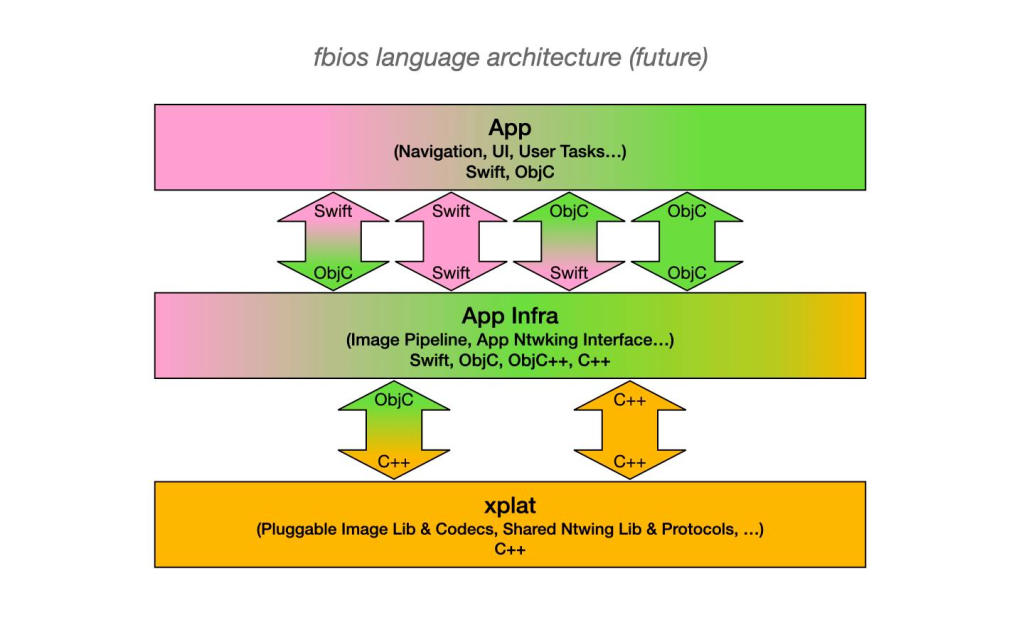

Here’s a diagram outlining the issues in the codebase:

With this in mind, we began to form a language strategy about when and where various bits of code should be used:

Ultimately, the FBiOS team began to advise that product-facing APIs/code should not contain C++ so that we could freely use Swift and future Swift APIs from Apple. Using plugins, FBiOS could abstract away C++ implementations so that they still powered the app but were hidden from most engineers.

This type of workstream signified a bit of shift in the way FBiOS engineers thought about building abstractions. Since 2014, some of the biggest factors in framework building have been contributions to app size and expressiveness (which is why ComponentKit chose Objective-C++ over Objective-C).

The addition of Swift was the first time these would take a backseat to developer efficiency, and we expect to see more of that in the future.

2022: The journey is 1 percent finished

Since 2014, FBiOS architecture has shifted quite a bit:

- It introduced countless in-house abstractions, like ComponentKit and GraphQL.

- It uses dylibs to keep ‘pre-main’ times minimal and contribute to a blazing-fast app startup.

- It introduced a plugin system (powered by Buck) so that dylibs are abstracted away from engineers, and so code is easily shareable between apps.

- It introduced language guidelines about when and where various languages should be used and began to shift the codebase to reflect those language guidelines.

Meanwhile, Apple has introduced exciting improvements to their phones, OS, and SDK:

- Their new phones are fast. The cost of loading is much smaller than it was before.

- OS improvements like dyld3 and chain fixups provide software to make code loading even faster.

- They’ve introduced SwiftUI, a declarative API for UI that shares a lot of concepts with ComponentKit.

- They’ve provided improved SDKs, as well as APIs (like interruptible animations in iOS8) that we could have built custom frameworks for.

As more experiences are shared across Facebook, Messenger, Instagram, and WhatsApp, FBiOS is revisiting all these optimizations to see where it can move closer to platform orthodoxy. Ultimately, we’ve seen that the easiest ways to share code are to use something that the app gives you for free or build something that is virtually dependency-free and can integrate between all the apps.

We’ll see you back here in 2032 for the recap of the codebase’s 20-year anniversary!