As one of the largest senders of email on the Internet, Facebook is also one of the largest phishing targets. After working at an ISP on email security and abuse issues for several years, I came to Facebook because I wanted to have a greater impact on the email ecosystem. Supported by Facebook’s commitment to open technologies, in 2010 I started working with a handful of other email security experts on a major anti-phishing effort called DMARC.

DMARC.org is a working group of industry experts from leading companies who came together to collaborate on an open specification for fighting domain spoofing. As a technology, DMARC is a new way to protect people from misleading and potentially malicious email. Previous attempts to provide similar protection had either been unsuccessful due to false positive issues, or had relied upon private agreements between companies. DMARC builds on those earlier experiences and leverages existing open technologies to provide a powerful, flexible, and open framework that any email system operator or domain owner can use.

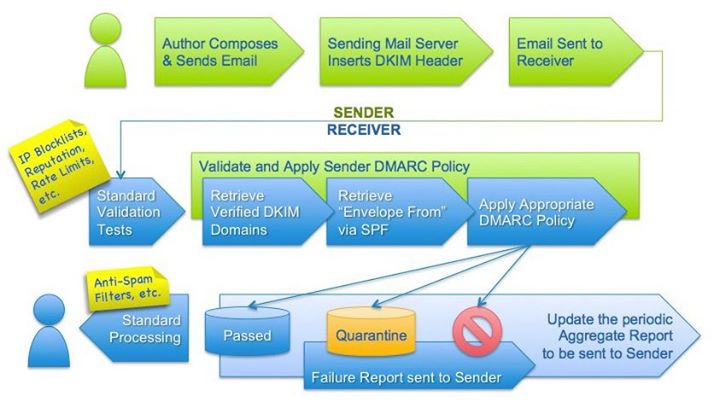

DMARC allows a domain owner to request aggregated, anonymized data from mailbox providers about email that appears to be from their domain. This allows the domain owner to gauge how serious their phishing problem is and lets them audit their own infrastructure for accurate deployment of DKIM and SPF, the two domain authentication technologies DMARC uses. Once they are sure all of their real email is authenticated, DMARC allows the domain owner to ask mailbox providers not to deliver unauthenticated email from their domain. The end result is that users won’t get email that claims to be from a facebook.com or facebookmail.com address unless it really is from Facebook.

This sort of verification might seem like it should be easy to do, but email has never had a scalable security model. It grew organically and became ubiquitous because it was so open and decentralized. No domain needed any knowledge of any other domain’s infrastructure to accept messages, so until the rise of email phishing there was no reason to try to build such functionality.

A wide variety of email software, configurations, and use cases have been developed over the years, and adding a new policy layer on top of such a large and diverse ecosystem must be done with a great deal of care. Operational complexity, false positives, and lack of the flexibility needed to support use cases like third-party delegation or automated forwarding can all create friction, and too much friction leaves people unwilling to deploy.

But DMARC has a few key features that differentiate it from previous attempts. Aggregate reports, which I feel are the real key to DMARC’s success, create an open way to gain unprecedented visibility into your domain’s email. Without this kind of visibility, it was very expensive and time consuming to audit your infrastructure, track your progress, and monitor your system for authentication issues. Now, we recommend that every domain owner publish a DMARC record to obtain these reports. Even if you don’t find evidence that someone is trying to impersonate your domain, you’ve still learned something about your infrastructure.

Since not everyone can jump into DMARC the way Facebook was able to, we’ve created options to help domain owners tailor their DMARC deployments to their infrastructures and roll it out slowly. Instead of simply being “on” or “off,” DMARC can be applied to a configurable percentage of domain traffic. This allows for a slow and progressive deployment while reducing the damage any issues might cause. Domain owners can also control whether the domain names in the email have to match, or whether they can be subdomains of one another. This is important because it allows enough flexibility to cover use cases like bounce-handling subdomains.

The only way DMARC could scale to a larger audience than the companies who created it was as an open specification. DMARC.org chose to use the Open Web Foundation Agreements for the specification, which Facebook already used for exactly this sort of collaboration. Having pre-existing agreements and a strong open philosophy makes it easy for us to participate in these kinds of efforts and really focus on the technical work without getting bogged down by approval processes.

The best part about DMARC is that it’s not just a proposed specification—it’s already in production. Since we’re encouraged to move fast and take risks here, once DMARC v1 was ready almost a year ago, Facebook published the first DMARC DNS records on the internet. At the time, Gmail was the only provider who was ready to query and act on DMARC records. Any issues could have caused some or all of our email to Gmail to not be delivered, and anywhere else, making a change that potentially disruptive would have required a lengthy review process and numerous approvals.

While we’ve taken a huge step toward creating a scalable system to make email secure, user trends like reusing passwords for multiple online services makes compromised accounts a serious problem. The current version of the DMARC specification works well, but there is always room for optimization, better documentation, handling unexpected edge cases, and reacting to the phishers’ next moves. We need more people who are willing to implement DMARC and share their experience so that we can continue improving it and providing more comprehensive protection. Sign up for the discussion list and get involved here.