Site speed is one of the most critical company goals for Facebook. In 2009, we successfully made Facebook site twice as fast, which was blogged in this post. Several key innovations from our engineering team made this possible. In this blog post, I will describe one of the secret weapons we used called BigPipe that underlies this great technology achievement. BigPipe is a fundamental redesign of the dynamic web page serving system. The general idea is to decompose web pages into small chunks called pagelets, and pipeline them through several execution stages inside web servers and browsers. This is similar to the pipelining performed by most modern microprocessors: multiple instructions are pipelined through different execution units of the processor to achieve the best performance. Although BigPipe is a fundamental redesign of the existing web serving process, it does not require changing existing web browsers or servers; it is implemented entirely in PHP and JavaScript.

Motivation

To understand BigPipe, it’s helpful to take a look at the problems with the existing dynamic web page serving system, which dates back to the early days of the World Wide Web and has not changed much since then. Modern websites have become dramatically more dynamic and interactive than 10 years ago, and the traditional page serving model has not kept up with the speed requirements of today’s Internet. In the traditional model, the life cycle of a user request is the following:

- Browser sends an HTTP request to web server.

- Web server parses the request, pulls data from storage tier then formulates an HTML document and sends it to the client in an HTTP response.

- HTTP response is transferred over the Internet to browser.

- Browser parses the response from web server, constructs a DOM tree representation of the HTML document, and downloads CSS and JavaScript resources referenced by the document.

- After downloading CSS resources, browser parses them and applies them to the DOM tree.

- After downloading JavaScript resources, browser parses and executes them.

The traditional model is very inefficient for modern web sites, because a lot of the operations in the system are sequential and can’t be overlapped with each other. Some optimization techniques such as delaying JavaScript downloading, parallelizing resource downloading etc. have been widely adopted in the web community to overcome some of the limitations. However, very few of these optimizations touch the bottleneck caused by the web server and browser executing sequentially. When the web server is busy generating a page, the browser is idle and wasting its cycles doing nothing. When web server finishes generating the page and sends it to the browser, the browser becomes the performance bottleneck and the web server cannot help any more. By overlapping the web server’s generation time with the browser’s rendering time, we can not only reduce the end-to-end latency but also make the initial response of the web page visible to the user much earlier, thereby significantly reducing user perceived latency. The overlapping of web server generation time and browser’s render time is especially useful for content-rich web sites like Facebook. A typical Facebook page contains data from many different data sources: friend list, new feeds, ads, and so on. In a traditional page rendering model a user would have to wait until all of these queries have returned data before building the final document and sending it to the user’s computer. One slow query holds up the train for everything else.

How BigPipe works

To exploit the parallelism between web server and browser, BigPipe first breaks web pages into multiple chunks called pagelets. Just as a pipelining microprocessor divides an instruction’s life cycle into multiple stages (such as “instruction fetch”, “instruction decode”, “execution”, “register write back” etc.), BigPipe breaks the page generation process into several stages:

- Request parsing: web server parses and sanity checks the HTTP request.

- Data fetching: web server fetches data from storage tier.

- Markup generation: web server generates HTML markup for the response.

- Network transport: the response is transferred from web server to browser.

- CSS downloading: browser downloads CSS required by the page.

- DOM tree construction and CSS styling: browser constructs DOM tree of the document, and then applies CSS rules on it.

- JavaScript downloading: browser downloads JavaScript resources referenced by the page.

- JavaScript execution: browser executes JavaScript code of the page.

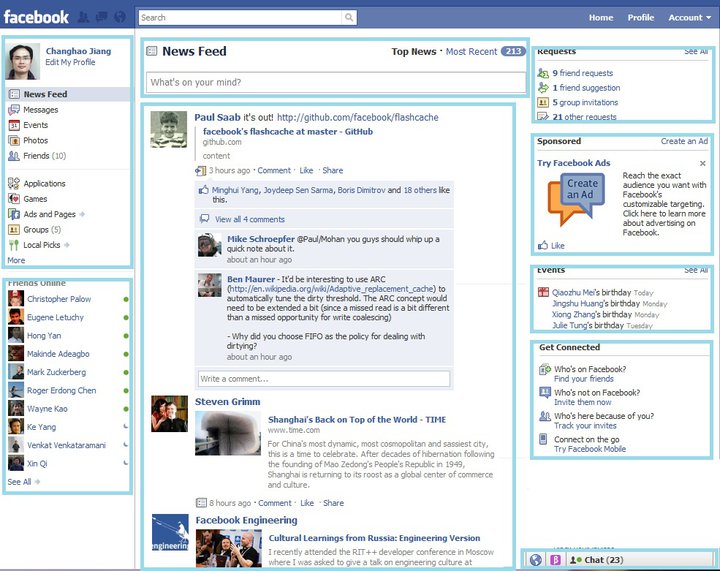

The first three stages are executed by the web server, and the last four stages are executed by the browser. Each pagelet must go through all these stages sequentially, but BigPipe enables several pagelets to be executed simultaneously in different stages.  The picture above uses Facebook’s home page as an example to demonstrate how web pages are decomposed into pagelets. The home page consists of several pagelets: “composer pagelet”, “navigation pagelet”, “news feed pagelet”, “request box pagelet”, “ads pagelet”, “friend suggestion box” and “connection box”, etc. Each of them is independent of each. When the “navigation pagelet” is displayed to the user, the “news feed pagelet” can still be being generated at the server. In BigPipe, the life cycle of a user request is the following: The browser sends an HTTP request to web server. After receiving the HTTP request and performing some sanity check on it, web server immediately sends back an unclosed HTML document that includes an HTML tag and the first part of the tag. The tag includes BigPipe’s JavaScript library to interpret pagelet responses to be received later. In the tag, there is a template that specifies the logical structure of page and the placeholders for pagelets. For example:

The picture above uses Facebook’s home page as an example to demonstrate how web pages are decomposed into pagelets. The home page consists of several pagelets: “composer pagelet”, “navigation pagelet”, “news feed pagelet”, “request box pagelet”, “ads pagelet”, “friend suggestion box” and “connection box”, etc. Each of them is independent of each. When the “navigation pagelet” is displayed to the user, the “news feed pagelet” can still be being generated at the server. In BigPipe, the life cycle of a user request is the following: The browser sends an HTTP request to web server. After receiving the HTTP request and performing some sanity check on it, web server immediately sends back an unclosed HTML document that includes an HTML tag and the first part of the tag. The tag includes BigPipe’s JavaScript library to interpret pagelet responses to be received later. In the tag, there is a template that specifies the logical structure of page and the placeholders for pagelets. For example: <p><div id=”left_column”> <div id=”pagelet_navigation”></p></p><div id=”middle_column”> <div id=”pagelet_composer”></p><div id=”pagelet_stream”></p></p><div id=”right_column”> <div id=”pagelet_pymk”></p><div id=”pagelet_ads”></p><div id=”pagelet_connect”></p></p></p> After flushing the first response to the client, web server continues to generate pagelets one by one. As soon as a pagelet is generated, its response is flushed to the client immediately in a JSON-encoded object that includes all the CSS, JavaScript resources needed for the pagelet, and its HTML content, as well as some meta data. For example: <script type="text/javascript"> big_pipe.onPageletArrive({id: “pagelet_composer”, content=<HTML>, css=[..], js=[..], …}) </script> At the client side, upon receiving a pagelet response via “onPageletArrive” call, BigPipe’s JavaScript library first downloads its CSS resources; after the CSS resources are downloaded, BigPipe displays the pagelet by setting its corresponding placeholder div’s innerHTML to the pagelet’s HTML markup. Multiple pagelets’ CSS can be downloaded at the same time, and they can be displayed out-of-order depending on whose CSS download finishes earlier. In BigPipe, JavaScript resource is given lower priority than CSS and page content. Therefore, BigPipe won’t start downloading JavaScript for any pagelet until all pagelets in the page have been displayed. After that all pagelets’ JavaScript are downloaded asynchronously. Pagelet’s JavaScript initialization code would then be executed out-of-order depending on whose JavaScript download finishes earlier. The end result of this highly parallel system is that several pagelets are executed simultaneously in different stages. For example, the browser can be downloading CSS resources for three pagelets while rendering the content for another pagelet, and meanwhile the server is still generating the response for yet another pagelet. From the user’s perspective, the page is rendered progressively. The initial page content becomes visible much earlier, which dramatically improves user perceived latency of the page. To see the difference for yourself, you can try the following links: Traditional model and BigPipe. The first link renders the page in the traditional single flush model. The second link renders the page in BigPipe’s pipeline model. The difference between the two pages’ load times will be much more significant if your browser version is old, your network speed is slow, and your browser cache is not warmed.

Performance results

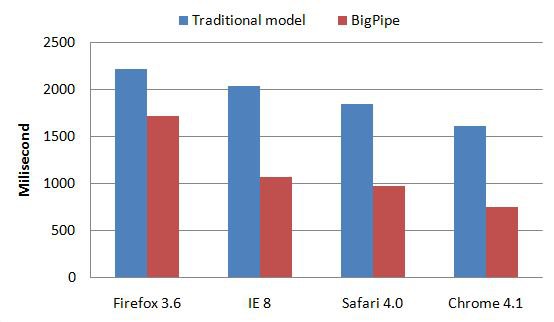

The graph below shows the performance data comparing the 75th percentile user perceived latency for seeing the most important content in a page (e.g. news feed is considered the most important content on Facebook home page) on traditional model and BigPipe. The data is collected by loading Facebook home page 50 times using browsers with cold browser cache. The graph shows that BigPipe reduces user perceived latency by half in most browsers.  It is worth noting that BigPipe was inspired by pipelining microprocessors. However, there are some differences between the pipelining performed by them. For example, although most stages in BigPipe can only operate on one pagelet at a time, some stages such as CSS downloading and JavaScript downloading can operate on multiple pagelets simultaneously, which is similar to superscalar microprocessors. Another important difference is that in BigPipe, we have implemented a ‘barrier’ concept borrowed from parallel programming, where all pagelets have to finish a particular stage, e.g. pagelet displaying stage, before any one of them can proceed further to download JavaScript and execute them. At Facebook, we encourage thinking outside the box. We are constantly innovating on new technologies to make our site faster.

It is worth noting that BigPipe was inspired by pipelining microprocessors. However, there are some differences between the pipelining performed by them. For example, although most stages in BigPipe can only operate on one pagelet at a time, some stages such as CSS downloading and JavaScript downloading can operate on multiple pagelets simultaneously, which is similar to superscalar microprocessors. Another important difference is that in BigPipe, we have implemented a ‘barrier’ concept borrowed from parallel programming, where all pagelets have to finish a particular stage, e.g. pagelet displaying stage, before any one of them can proceed further to download JavaScript and execute them. At Facebook, we encourage thinking outside the box. We are constantly innovating on new technologies to make our site faster.

Changhao Jiang is a Research Scientist at Facebook who enjoys making the site faster in innovative ways.