Over time, the software industry has come up with several ways to deliver code faster, safer, and with better quality. Many of these efforts center on ideas such as continuous integration, continuous delivery, agile development, DevOps, and test-driven development. All these methodologies have one common goal: to enable developers to get their code out quickly and correctly to the people who use it, in safe, small, incremental steps.

The development and deployment processes at Facebook have grown organically to encompass many parts of these rapid iteration techniques without rigidly adhering to any one in particular. This flexible, pragmatic approach has allowed us to release our web and mobile products successfully on rapid schedules.

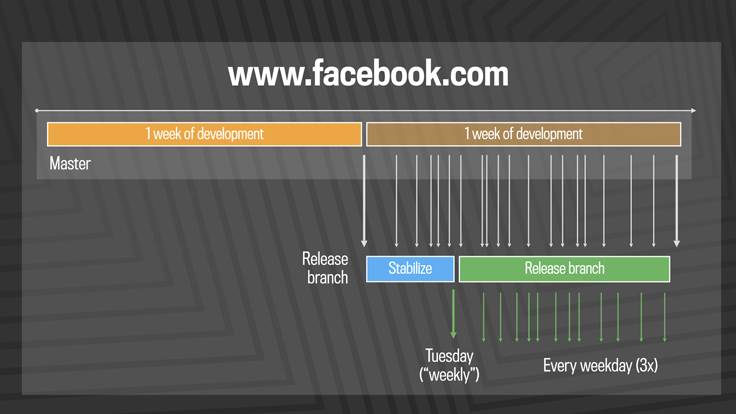

For many years, we pushed the Facebook front end three times a day using a simple master and release branch strategy. Engineers would request cherry-picks — changes to the code that had passed a series of automated tests — to pull from the master branch into one of the daily pushes from the release branch. In general, we saw between 500 and 700 cherry-picks per day. Once a week, we’d cut a new release branch that picked up any changes that were not cherry-picked during the week.

This system scaled well, starting with a handful of engineers in 2007 to thousands today. The good news is that as we added more engineers, we got more done — the rate of code delivery scaled with the size of the team. But it took a certain amount of human effort in the form of release engineers, in addition to the tools and automated systems in place, to drive the daily and weekly pushes out the door. We understood that batching up larger and larger chunks of code for delivery would not continue to scale as the team kept growing.

By 2016, we saw that the branch/cherry-pick model was reaching its limit. We were ingesting more than 1,000 diffs a day to the master branch, and the weekly push was sometimes as many as 10,000 diffs. The amount of manual effort needed to coordinate and deliver such a large release every week was not sustainable.

We decided to move facebook.com to a quasi-continuous “push from master” system in April 2016. Over the next year, we gradually rolled it out, first to 50 percent of employees, then from 0.1 percent to 1 percent to 10 percent of production web traffic. Each of these progressions allowed us to test the ability of our tools and processes to handle the increased push frequency and get real-world signal. Our main goal was to make sure that the new system made people’s experience better — or at the very least, didn’t make it worse. After almost exactly a year of planning and development, over the course of three days in April 2017 we enabled 100 percent of our production web servers to run code deployed directly from master.

Continuous delivery at scale

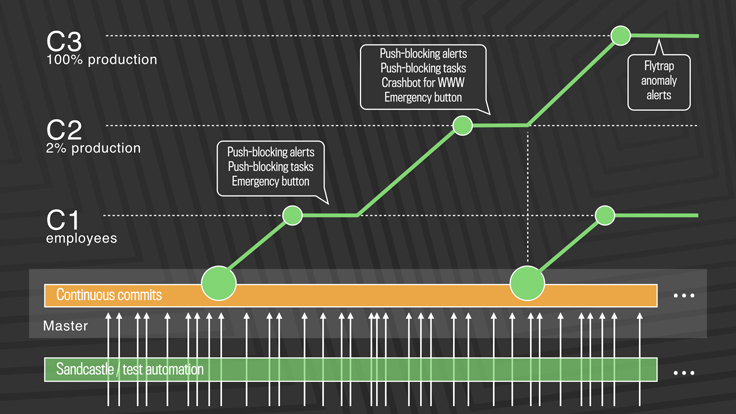

While a true continuous push system would deliver every individual change to production soon after it landed, the code velocity at Facebook required us to develop a system that pushes tens to hundreds of diffs every few hours. The changes that get made in this quasi-continuous delivery mode are generally small and incremental, and very few will have a visible effect on the actual user experience. Each release is rolled out to 100 percent of production in a tiered fashion over a few hours, so we can stop the push if we find any problems.

First, diffs that have passed a series of automated internal tests and land in master are pushed out to Facebook employees. In this stage, we get push-blocking alerts if we’ve introduced a regression, and an emergency stop button lets us keep the release from going any further. If everything is OK, we push the changes to 2 percent of production, where again we collect signal and monitor alerts, especially for edge cases that our testing or employee dogfooding may not have picked up. Finally, we roll out to 100 percent of production, where our Flytrap tool aggregates user reports and alerts us to any anomalies.

Many of the changes are initially kept behind our Gatekeeper system, which allows us to roll out mobile and web code releases independently from new features, helping to lower the risk of any particular update causing a problem. If we do find a problem, we can simply switch the gatekeeper off rather than revert back to a previous version or fix forward.

This quasi-continuous release cycle comes with several advantages:

It eliminates the need for hotfixes. In the three-push-a-day system, if a critical change had to get out and it wasn’t during one of the scheduled push times, someone had to call for a hotfix. These out-of-band pushes were disruptive because they usually needed some human action and could bump into the next scheduled push. With the new system, the vast majority of things that would have required a hotfix can simply be committed to master and pushed in the next release.

It allows better support for a global engineering team. We tried to schedule the three daily pushes to accommodate our engineering offices around the world, but even with that effort the weekly push required all engineers to pay attention at a specific date and time that was not always convenient in their time zone. The new quasi-continuous system means all engineers everywhere in the world can develop and deliver their code when it makes sense for them.

It provides a forcing function to develop the next generation of tools, automation, and processes necessary to allow the company to scale. When we take on projects like this, it works as a pressure test across many teams and systems. We made improvements to our push tools, our diff review tools, our testing infrastructure, our capacity management system, our traffic routing systems, and many other areas. These teams all came together because they wanted to see the main project of a faster push cycle succeed. The improvements we made will help ensure the company is ready for future growth.

It makes the user experience better, faster. When it takes days or weeks to see how code will behave, engineers may have already moved on to something new. With continuous delivery, engineers don’t have to wait a week or longer to get feedback about a change they made. They can learn more quickly what doesn’t work, and deliver small enhancements as soon as they are ready instead of waiting for the next big release. From an infrastructure perspective, this new system puts us in a much better position to react to rare events that might impact people. Ultimately, this brings engineers closer to users and improves both product development and product reliability.

Bringing continuous delivery to mobile

Evolving to a quasi-continuous system on the web was possible in part because we own the entire stack and could build or improve the tools we needed to make it a reality. Shipping on mobile platforms presents more of a challenge, as many of the current development and deployment tools available for mobile make rapid iteration difficult.

Facebook has worked to make this better by building and open-sourcing a wide set of tools that focus specifically on rapid mobile development, including Nuclide, Buck, Phabricator, a variety of iOS libraries, React Native, and Infer. Together, this build and test stack gives us the ability to produce quality code that’s ready for rapid deployment to mobile platforms.

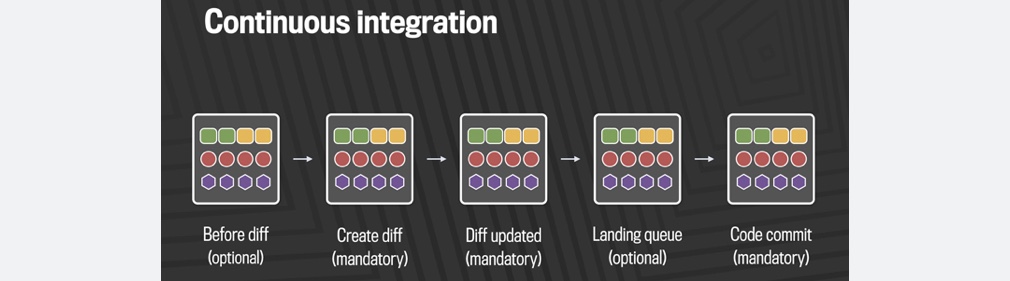

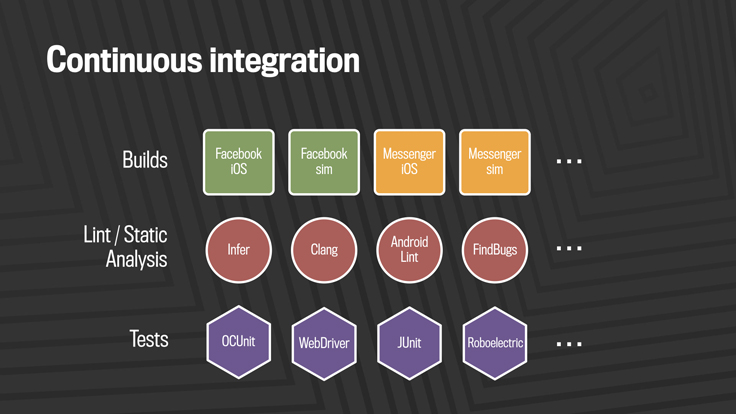

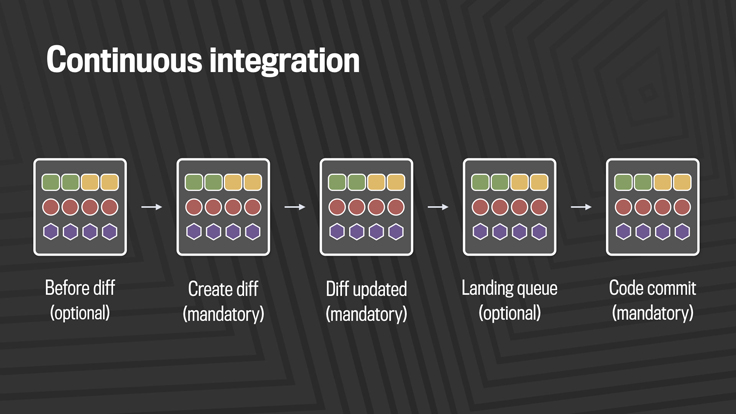

Our continuous integration stack is broken down into three layers: builds, static analysis, and testing.

Whenever code is committed from a developer branch into our mobile master branches, it first is built across all products the code could affect. For mobile, this means building Facebook, Messenger, Pages Manager, Instagram, and other apps on every commit. We also build several flavors of each product to ensure we’ve covered all the chip architectures and simulators those products support.

While the builds are going, we run linters and our static analysis tool, Infer. These will help catch null pointer exceptions, resource and memory leaks, unused variables, and risky system calls, and will flag Facebook coding guideline issues.

The third concurrent system, mobile automated testing, includes thousands of unit tests, integration tests, and end-to-end tests driven by tools like Robolectric, XCTest, JUnit, and WebDriver.

This build and test stack not only runs on every commit, but also runs multiple times during the life cycle of any code change. On Android alone, we do between 50,000 and 60,000 builds a day.

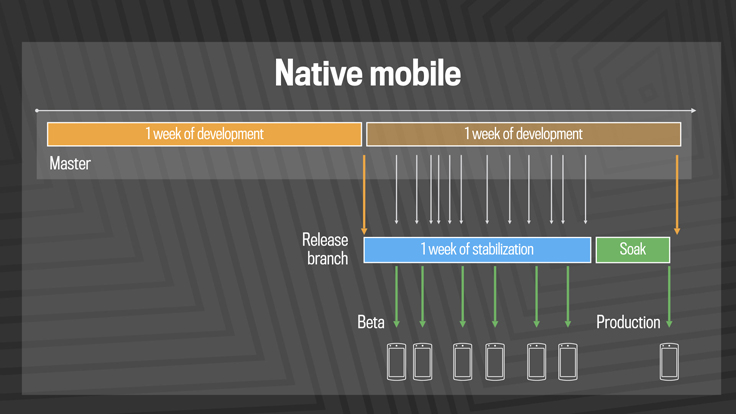

By applying traditional continuous delivery techniques to our mobile stack, we’ve gone from four-week releases to two-week releases to one-week releases. Today we use the same kind of branch/cherry-pick model on mobile that we previously used on web. Although we push to production only once a week, it’s still important to test the code early in real-world settings so that engineers can get quick feedback. We make mobile release candidates available every day for canary users, including 1 million or so Android beta testers.

At the same time we’ve increased our release frequency, our mobile engineering teams have grown by a factor of 15, and our code delivery velocity has increased considerably. Despite this, our data from 2012 to 2016 shows that engineer productivity remained constant for both Android and iOS, whether measured by lines of code pushed or the number of pushes. Similarly, the number of critical issues arising from mobile releases is almost constant regardless of the number of deployments, indicating that our code quality does not suffer as we continue to scale.

With so many advances in available tools and methodologies, it’s an exciting time to be working in the area of release engineering. I’m very proud of the teams at Facebook that have worked together to give us what I think is one of the most advanced web and mobile deployment systems at this scale. Part of what made this all possible is having a strong, central release engineering team that’s a first-class citizen in the infrastructure engineering space. The release team at Facebook will continue to drive initiatives that improve the release process for developers and customers, and we’ll continue to share our experiences, tools, and best practices.