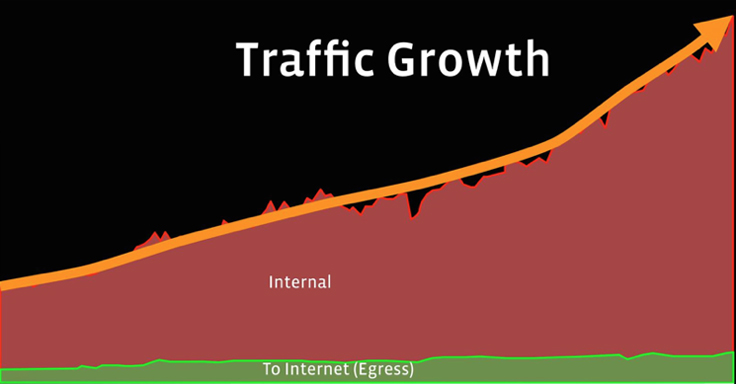

Facebook has multiple data centers in the U.S and Europe. For the past ten years, they were connected by a single wide-area (WAN) backbone network known as the classic backbone or CBB. This network carried both user (egress) traffic and internal server-to-server traffic.

In recent years, bandwidth demand for cross-data center replication of rich content like photos and video has been increasing rapidly, challenging the efficiency and speed of evolution of the classic backbone.

Furthermore, machine-to-machine traffic often occurs in large bursts that may interfere with and impact the regular user traffic, affecting our reliability goals. As new data centers were being built, we realized the need to split the cross-data center vs Internet-facing traffic into different networks and optimize them individually. In a less than a year, we built the first version of our new cross-data center backbone network, called the Express Backbone (EBB), and we’ve been growing it ever since.

Network design

As we started to build a new network, it felt right to improve upon some of the technical constraints of the “classic” backbone network. We set the following high-level goals for the project:

- Find a design allowing for incremental deployment of new features and code updates, preferably in fractional units of network capacity to allow for fast iterations.

- Avoiding pitfalls with distributed traffic engineering (RSVP-TE based Auto-Bandwidth), such as inefficient use of network resources and complex convergence patterns under network failures.

- Keep network state lean by leveraging MPLS segment routing at the edges of the network domain.

Interestingly enough, one of the insights to making the above happen was following some of the design patterns we use in our data center networks. Keeping the number of network prefixes small (on the order of thousands) in the new network enabled us to leverage commodity network gear. And splitting the physical topology network into four parallel topologies (known as “planes”) was directly based on the idea of our existing “four plane” data center network fabric.

Our very first iteration of the new network was built using a well-understood combination of an IGP and a full mesh iBGP topology to implement basic packet routing. The next step was adding a traffic-matrix estimator and central controller to perform traffic engineering functions assuming “static” topology. The final iteration replaced the “classical” IGP with an in-house distributed networking platform called Open/R, fully integrating the distributed piece with the central controller. At every iteration, we had the option to fall back to the most basic model, which provided a good safety cushion for experimentation.

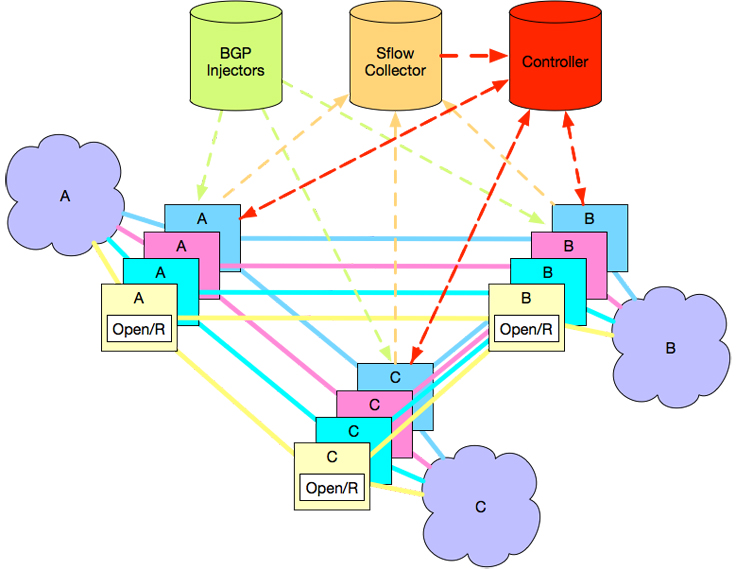

Below is a diagram illustrating the design with a simplified three-site topology example. The full control stack consists of few main components:

- Centralized (and highly redundant) ensemble of BGP-based route injectors to move traffic on/off the network

- sFlow collector, based on collecting sFlow samples from the network devices, used to feed in active demands into the traffic engineering controller

- Traffic engineering controller, which computes and programs optimum routes based on the current demand set.

- Open/R agents running on network devices to provide IGP and messaging functionality.

- LSP agents, also running on network devices to interface with the device forwarding tables on behalf of the central controller.

The hybrid software design along with clean fault domain splitting was part of what allowed the smooth evolution of the EBB project. Being able to conduct A/B testing between the planes (where each plane receives equal proportions of traffic) helped achieve rapid iterations. The ability to conduct experiments remains useful as it allows us to continually evolve our algorithms and perform fast upgrades/rollbacks with minimum disruption to live traffic.

Software design

Centralized or distributed?

As mentioned, EBB uses a hybrid model for traffic engineering (TE), having both distributed control agents and a central controller. This model allows us to control some aspects of traffic flow centrally, e.g., running intelligent path computations. At the same time, we still handle network failures in a distributed fashion, relying on in-band signaling between Open/R agents deployed on the network nodes.

Such a hybrid approach allows the system to be nimble when it encounters congestion or failure. In EBB, the local agents can immediately begin redirecting traffic when they spot an issue (local response). The central system then has time to evaluate the new topology and come up with an optimum path allocation, without the urgent need to react rapidly.

Open/R

We discover the live network state by running Open/R agents on the network devices. Open/R is the distributed application development platform Facebook introduced last year, providing both the interior routing and the message bus for the Express Backbone network. The LSP agents learn of topology changes in real-time via the Open/R message bus and react locally. The central controller also interfaces with the Open/R agents for the purpose of the full network state discovery.

Traffic matrix estimator

The central controller needs the real-time traffic matrix to compute optimal paths in EBB network. Traffic matrix computation is based on sFlow samples exported by each network device and performed by the traffic matrix estimation service. The service passively collects the samples, aggregates them per source/destination data center pair for each traffic class, and produces a complete traffic matrix per traffic class for controller to consume. Naturally, the traffic matrix is smoothed in time, and the smoothing interval could be set differently per traffic class.

LSP agents

LSP agents, first and foremost, provide a Thrift-based API to the Controller for pushing the MPLS segment routes down to the network hardware’s forwarding tables. Furthermore, upon network failures, each LSP agent evaluates whether its LSPs are affected and if needed will fail over to the backup path. The fail over typically occurs within hundreds of milliseconds, and serves as a first line of defense against network outages.

Controller

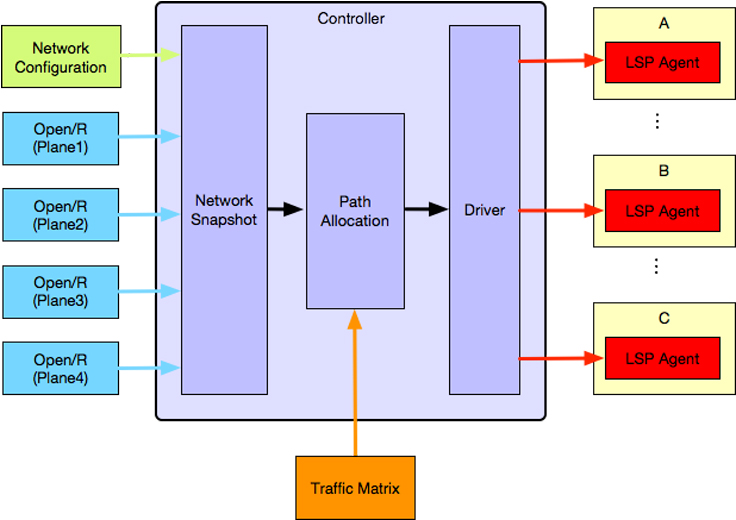

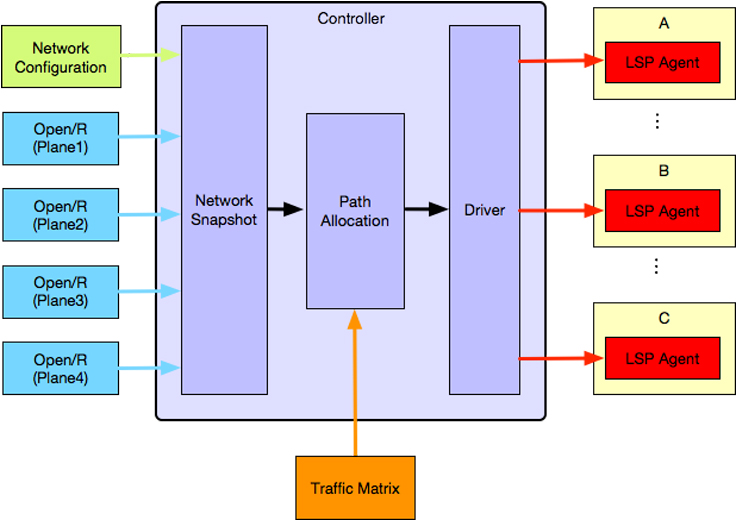

The traffic engineering controller consists of three main modules:

- Network State Snapshot module, responsible for building active network state and traffic matrix.

- Path Allocation module, responsible for computing abstract source routes based on active traffic matrix and satisfying certain optimality criteria.

- Driver module, responsible for pushing the source routes computed by the Path Allocation module to the network devices in the form of MPLS segment routes.

Workflow

The controller operates in periodic cycles. Every cycle it builds a full snapshot of the network state, by collecting the topology graph and traffic matrix from the Open/R message bus and the Traffic Matrix Estimator service respectively. Acting on these inputs is pluggable path allocation algorithm, which decides the appropriate path for traffic to take in the network. The path allocation algorithm can be changed to address the different path requirements for each class of traffic. For example, it can:

- Minimize latency for latency-sensitive traffic.

- Minimize path congestion for latency-insensitive traffic.

- Schedule latency-sensitive traffic ahead of latency-insensitive traffic.

The path allocation algorithm (running on the controller) creates MPLS LSP meshes (a collection of LSPs connecting all data-centers) over the current topology that can carry the demanded traffic. There is one LSP mesh per traffic class. LSPs are bundled between each data center pair and each LSP is given a primary and backup path (that is most path diverse).

After the LSP meshes are allocated, the driver programs them into routers by sending instructions to LSP agents, converting LSP paths to label stacks. Using segment routing (SR), we only need to program the label stack in the headend (source) router. This simplifies programming and improves robustness.

Lessons learned

We’ve learned a great deal about network design while building and implementing EBB. While we uncovered new challenges, such as going through growth pains of keeping the network state consistent and stable, the centralized real-time scheduling has proven to be simple and efficient in the end.

Some of the new challenges we had to address included introducing new software components (controller, traffic estimator, and agents), debugging inconsistent states across different entities, debugging packet loss and diagnosing bad LSPs.

Benefits of our approach include creation of our own TE scheme, improved visibility of traffic demand and the correspondingly allocated LSPs, failure simulation, and a simple multi-plane architecture.

What’s next?

We’re very excited to have EBB running in production, but we are continuously looking to make further improvements to the system. For example, we’re extending the controller to provide a per-service bandwidth reservation system. This feature would make bandwidth allocation an explicit contract between the network and services, and would allow services to throttle their own traffic under congestion. In addition, we’re also working on a scheduler for large bulk transfers so that congestion can be avoided proactively, as opposed to managed reactively.

Many people contributed to this project, but the core team members, all of whom were instrumental in making this project happen are – Omar Baldonado, Neda Beheshti, Brandon Bennett, Adam Cooley, Mayuresh Gaitonde, Prabhakaran Ganesan, Nitin Goel, Saif Hasan, Sandeep Hebbani, Mikel Jimenez, Henry Kwok, Petr Lapukhov, Chiun Lin Lim, Mark McKillop, Natalie Mead, Gaya Nagarajan, Alexander Nikolaidis, Giuseppe Rizzelli, Krishna Sarath, Songqiao Su, David Swafford, Vladislav Vasilev, Jimmy Williams, and Shuqiang Zhang.