- In this post, we explore the ways we’re evolving Meta’s data warehouse to facilitate productivity and security to serve both human users and AI agents.

- We detail how we’re developing agents that help users making data access requests to get to the data they need, and that help data owners process requests and maintain security.

- We share how we’re using guardrails, including auditing and feedback systems, to ensure agents operate within set boundaries and to evaluate the overall process.

As part of its offline data systems, Meta operates a data warehouse that supports use cases across analytics, ML, and AI. Given the sheer volume of data, the scale of our systems, and the diverse use cases built on top, data warehouse security is very important. Teams across Meta both manage access and use that data in their day-to-day work. As the scale continues to grow and the data access patterns become more complex, the complexity of managing access and the time spent to obtain access keep increasing. How do we minimize security risks and enable teams to operate efficiently? With the rise of GenAI and agents, we needed to rethink how we can enhance security and productivity with agents, making them an integral part of our internal data products, capable of both streamlining data access and minimizing risk. In this post, we will share our work.

Background

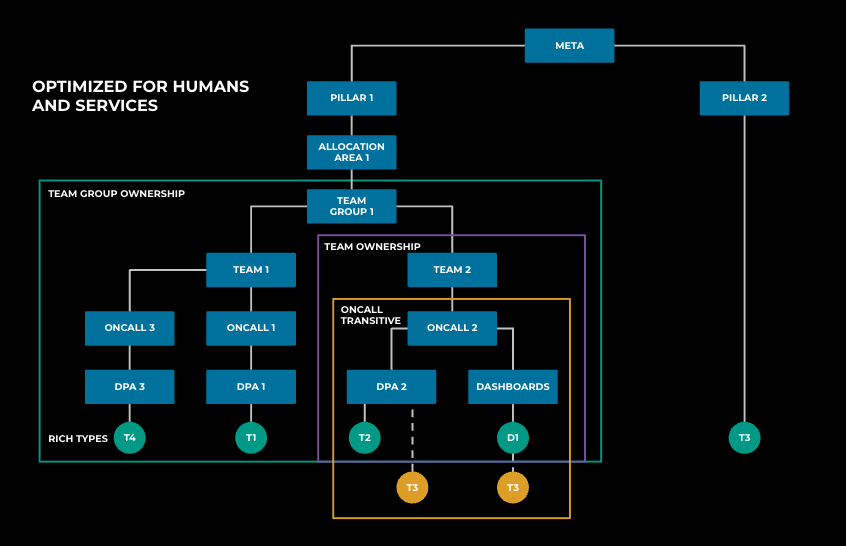

In the past, we scaled data access and management by organizing the data warehouse into a hierarchical structure, as shown below in Figure 1. At the leaf of this hierarchy are tables, with pipelines producing them and dashboards consuming them. On-calls manage these assets, followed by teams and organizational hierarchies. Using role-based access control, we further modeled business needs as roles, aligning with this hierarchical structure and other dimensions, such as data semantics.

However, with the growth in AI, timely access of data has become increasingly important. As the scale of data warehouses continues to grow and data access patterns become more complex, the complexity and amount of time spent on managing and obtaining access keep increasing.

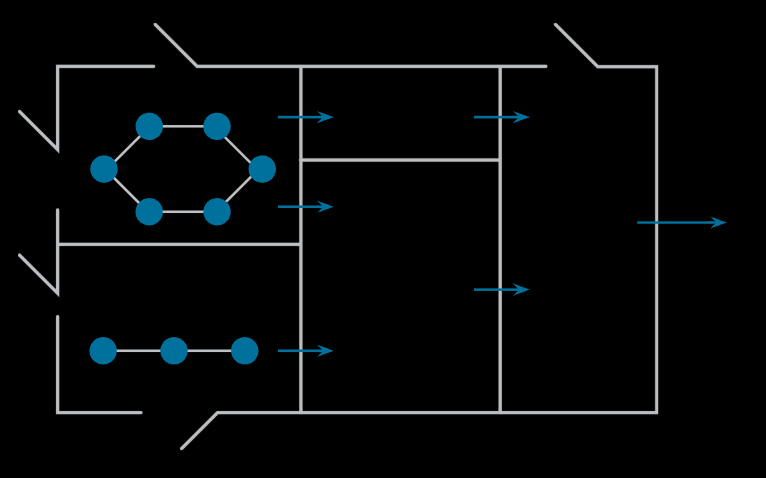

To understand how we have handled this traditionally, and why that is becoming increasingly challenging, it helps to visualize the data flow through Meta’s offline infrastructure as a graph, as shown in Figure 2 below. Each node in this graph is an asset, such as a table, a column, or a dashboard, and each edge in this graph is an activity.

Traditionally, when most of the data analytics was rules-driven, this graph was highly partitioned, and all data-access decisions were local. Engineers who wanted to use the data could discover the data by asking their teammates or looking at other people’s code. On the access-approval front, access could be granted to members of closely related teams. But with the ability of AI systems to process data across different portions of the data graph, such human-driven decisions are becoming challenging.

Figure 3 below illustrates that as humans and agents work more frequently across domains, the system complexity increases, both in terms of data scale and the dynamics of access, with AI being a major driver of these complex access patterns. However, we believe AI can also offer solutions to these challenges. With recent advancements in AI, particularly with agents, we’ve needed to evolve our previous approach to an agentic solution for data access. Additionally, while the system was originally designed for humans to operate and to serve both humans and services, we needed to adapt it for agents and humans working together. The new agentic workflow must natively integrate into data products and create a streamlined experience. We also must create strict guardrails, such as analytical rule-based risk assessment, to safeguard the agents.

User and owner agents

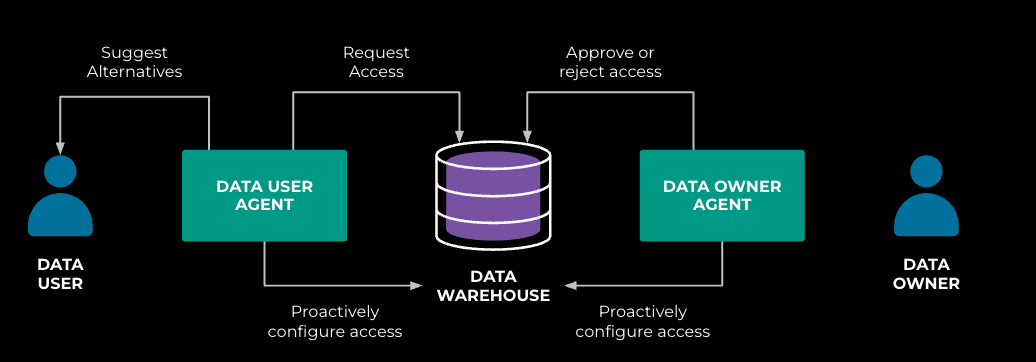

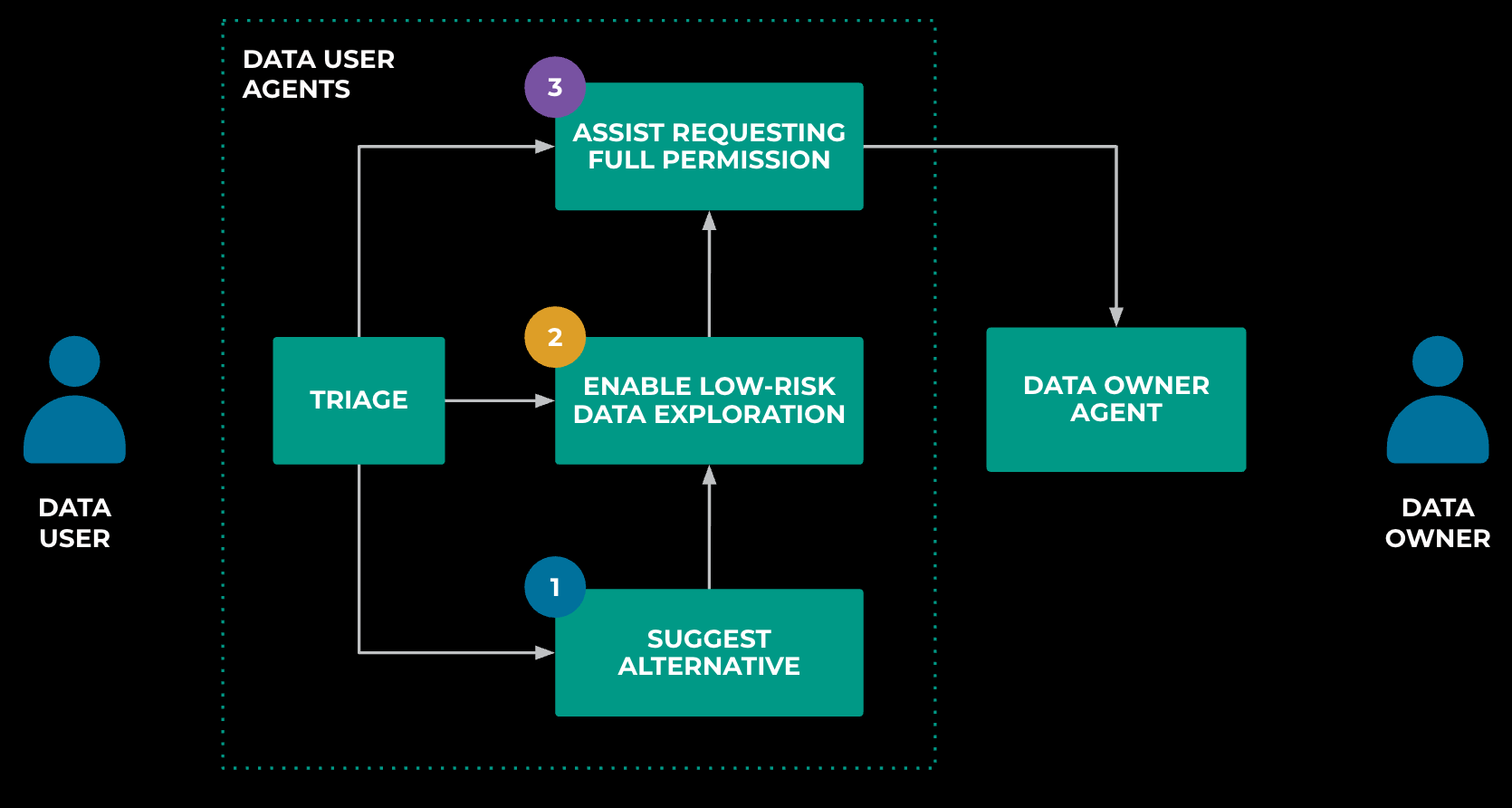

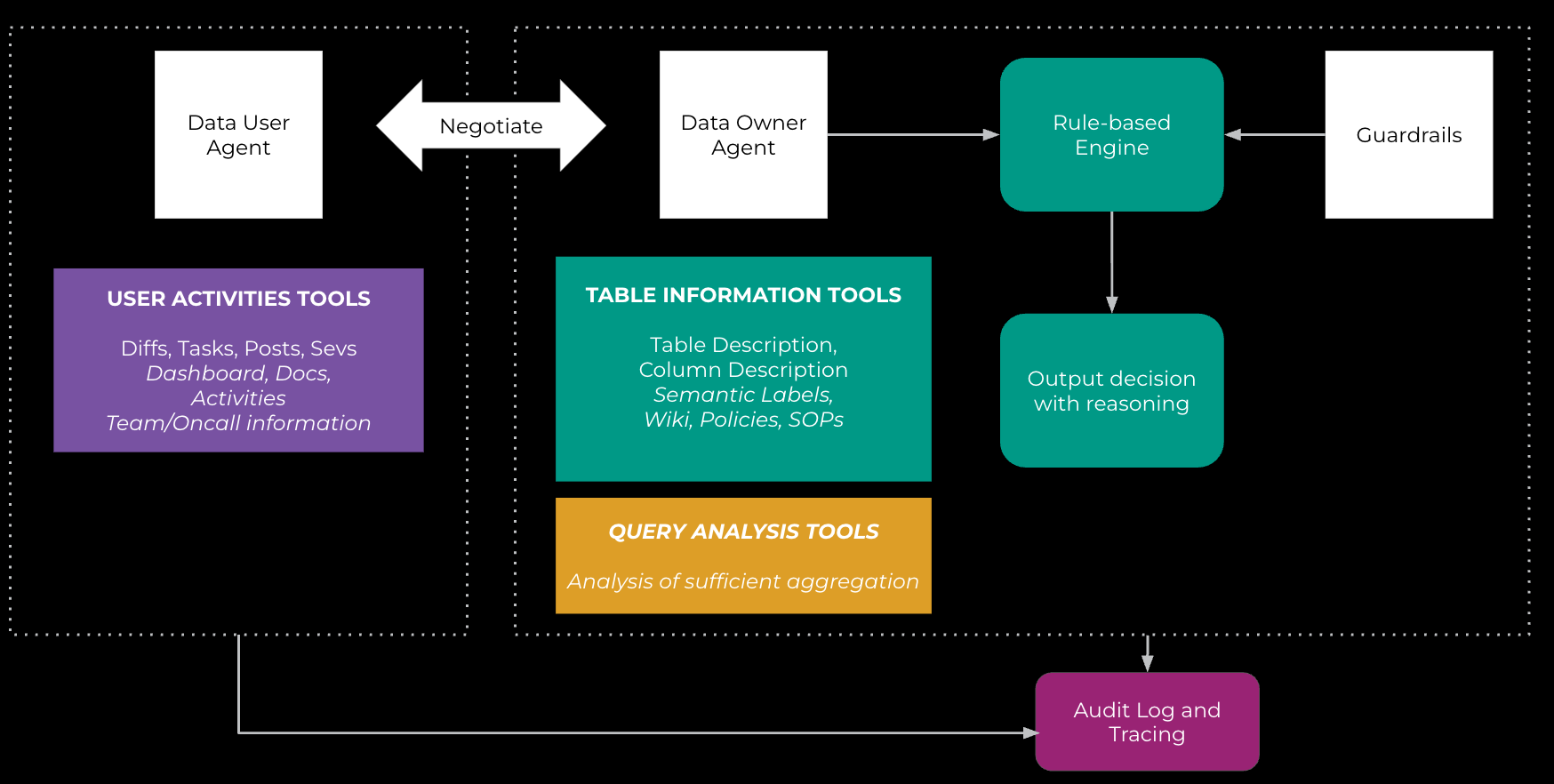

We modeled the solution as a multi-agent system, as shown in Figure 4 below. Data-user agents assist data users in obtaining access, while data-owner agents help data owners manage access. These two agents also collaborate to streamline the process when both parties are involved. We intentionally separate the two agents to decompose the problem, allowing each to have its own focus.

Look closer at the data-user agent illustrated below in Figure 5. It’s not a monolithic entity; instead, it’s composed of three specialized sub-agents, each focusing on a specific, separate task, and is coordinated by a triage agent.

The first sub-agent suggests alternatives. For instance, when users encounter restricted tables, alternative options are often available, including unrestricted or less-restrictive tables. The agent also assists users in rewriting queries to use only non-restricted columns or in utilizing curated analyses. These insights are often hidden or considered tribal knowledge. Large language models and agents allow us to synthesize this information and guide users at scale.

The second sub-agent facilitates low-risk data exploration. Typically, users often need access to only a small fraction of a table’s data, especially during the data-exploration phase of analysis workflows. This sub-agent provides context-aware, task-specific data access for low-risk exploration. We will dive deeper into this below.

The third sub-agent helps users obtain access by crafting permission requests and negotiating with data-owner agents. Currently, we maintain a human-in-the-loop for oversight, but over time, we expect these sub-agents will operate more autonomously.

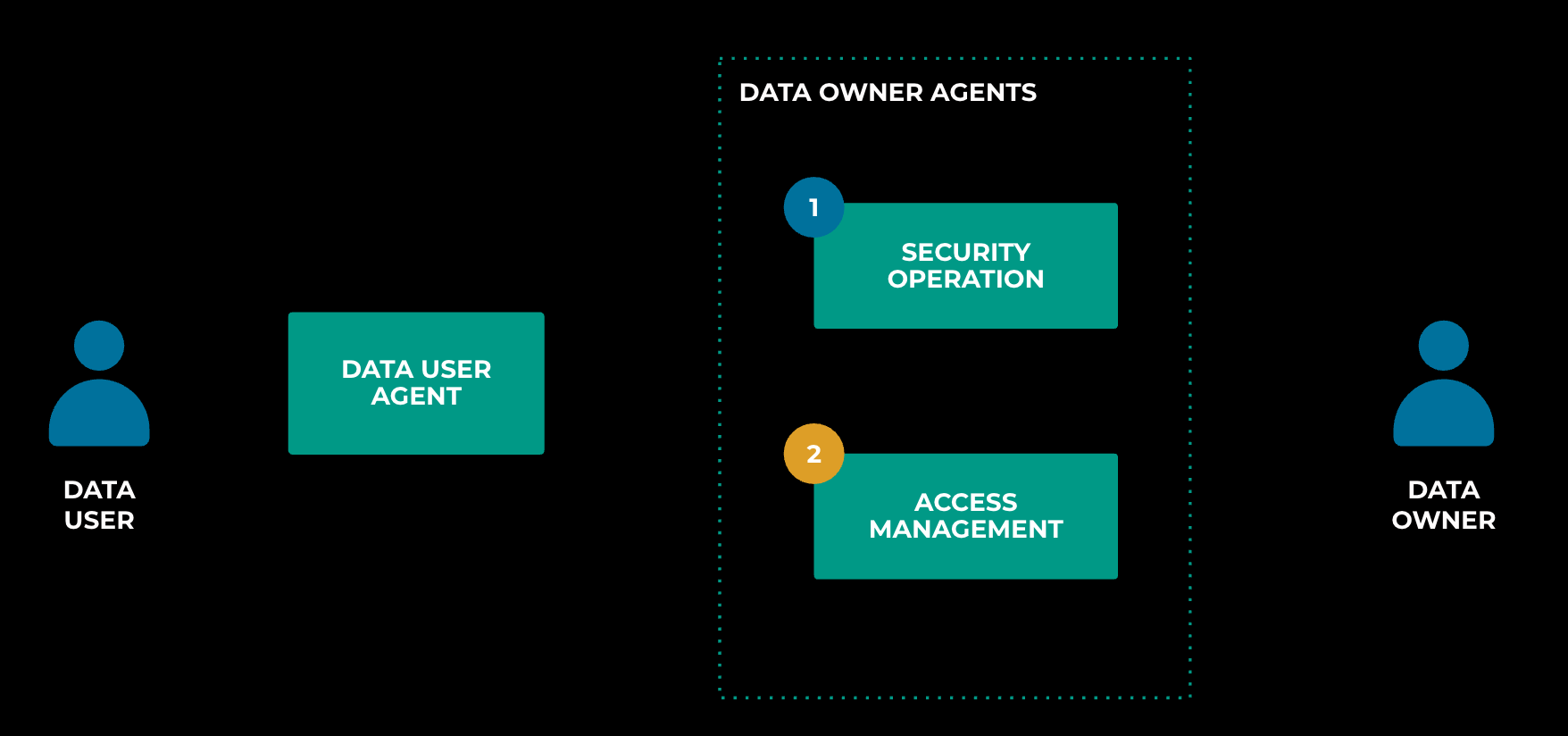

The data-owner agent is also composed of several sub-agents, including one for handling security operations and another for assisting with access management, as shown below in Figure 6.

The first data-owner sub-agent, focused on security operations, acts like a junior engineer who assists the team with security tasks. It follows the SOP (standard operating procedure) provided by the data owner, typically derived from documented rules or guidelines, to handle incoming permission requests.

The second sub-agent proactively configures access rules for the team. This represents an evolution from the traditional role-mining process, where agents enable us to better utilize semantics and content.

Data warehouse for agents

As we mentioned at the outset, we organized the data warehouse in a hierarchical structure to scale out access. How do we evolve it with the agentic system?

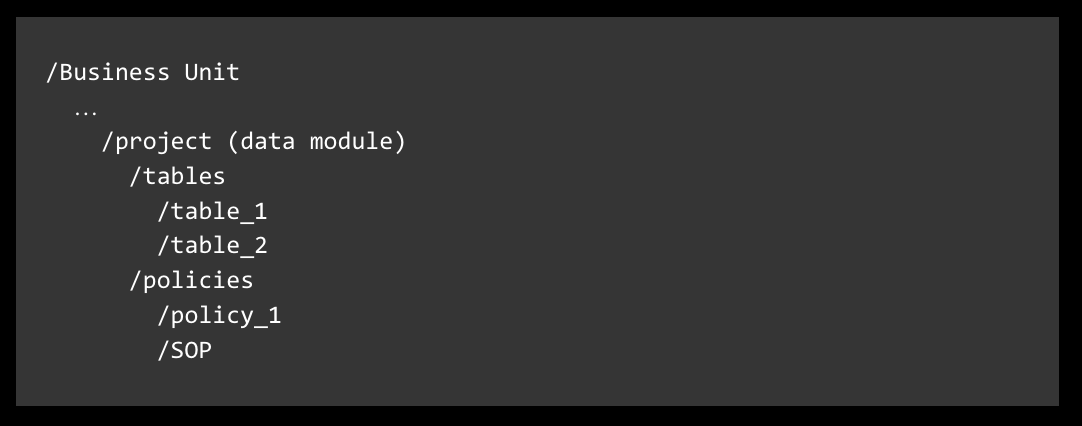

LLMs communicate through text. The hierarchical structure of the data warehouse provides a convenient way to convert warehouse resources into text, much like a nested folder structure, as depicted in Figure 7 below. Here, organizing units are represented as folders, while leaf nodes such as tables, dashboards, policies, or other entities are represented as resources. This setup gives agents a read-only summarized view of the data warehouse. The SOP we discussed earlier, which documents data-access practices from rules, wikis, and past interactions, becomes a resource that can be represented in text format. It serves as input for both data-user agents to guide users and data-owner agents to manage access.

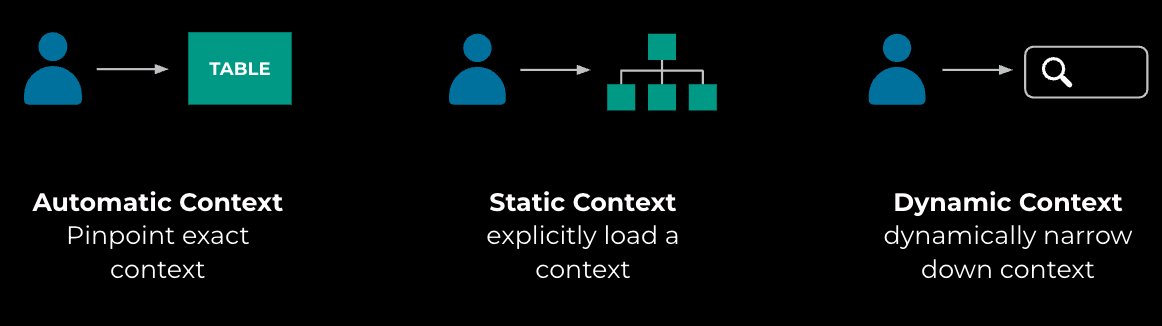

In addition to organizing inputs for agents to use, another crucial aspect is context management. Here, we differentiate among three scenarios, as shown below in Figure 8. The first scenario is called “automatic context.” Imagine data users discovering data they want to access, only to find their access blocked by controls. The system is aware of who is trying to access what, allowing the agent to fetch the exact context. The second scenario is “static context.” This occurs when users choose to focus on a specific scope explicitly or expand the resource from an automatic context to a broader one. The last scenario is “dynamic context.” It allows agents to further filter resources by metadata, such as data semantics, or via similarity search.

Another key area is intention management. In the context of data access, we often refer to this as “business needs.” What drives a data user to access certain resources? As shown in Figure 9 below, we model user intention in two ways: explicit and implicit.

In explicit intention management, users explicitly communicate their intentions to the system. For example, when using certain data tools to access data, they can inform the system of their current task by assuming an associated role, which carries the context of the business needs. This approach captures standard intentions.

The second is implicit intention. Not every intention can be modeled by roles. That’s where dynamic intention comes in. The system infers intention from a data user’s activities over a short period. For example, if a data user is woken up at midnight to address a pipeline failure, any subsequent data access is likely related to resolving that issue.

Deep dive: Partial data preview

Now, let’s dive into how all these elements come together to enable a complete end-to-end use case, which we refer to as partial data preview.

To quickly recap: In our data-access agentic solution, we have data-user agents that assist data users in obtaining access, and data-owner agents that help data owners manage and operate data access. Typically, a data user’s workflow begins with data discovery, followed by data exploration, before diving into full-fledged data analysis. During the exploration phase, there’s usually interaction with a small amount of data exposure. So, how do we enable more task-specific, context-aware access at this stage of data access?

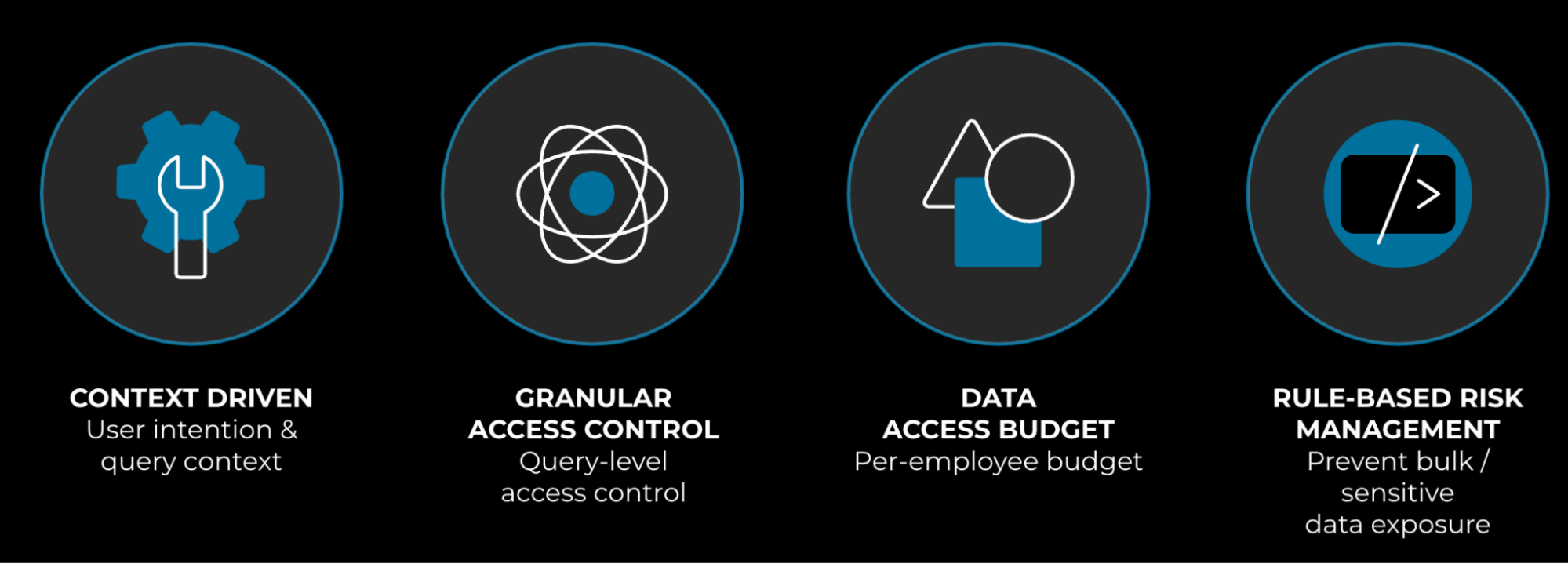

To make the system work seamlessly end to end, four key capabilities (illustrated below in Figure 10) are orchestrated by an agentic workflow:

- Context. We analyze data-user activities and other information to understand the business needs driving data access and align them with data controls. This enables us to provide task-specific, context-aware control.

- Query-level access control at a granular level. We analyze the shape of queries, such as whether they involve aggregation or random sampling.

- Data-access budget. Employees are given a data-access budget based on the amount of data they typically access, and this budget, which refreshes daily, is our first line of defense.

- Rule-based risk management. We employ rule-based risk control. This defends against attacks against or malfunctions of the AI agent.

Figure 11, below, illustrates how the system architecture works: The data-user agent taps into the user-activities tool to gather user activities across various platforms, including diffs, tasks, posts, SEVs, dashboards, and documents. It also uses the user-profile tool to fetch profile information. With this data, the data-user agent formulates the user’s intention based on their activities, profiles, and query shapes, and then calls upon the data-owner agent. The data-owner agent steps in to analyze the query, identifying the resources being accessed. It then fetches metadata related to these resources, such as table summaries, column descriptions, data semantics, and SOPs. The data-owner agent leverages an LLM model to generate the output decision and the reasoning behind it. The output guardrail ensures that the decision aligns with rule-based risk calculations.

All decisions and logs are securely stored for future reference and analysis. While many of these building blocks might be familiar to some of you—after all, we’ve been working with query analyzers for decades—this is the first time we’re harnessing the language and reasoning capabilities of LLMs to build a multi-agent system for data users and data owners. LLMs have shown potential in this area because business needs are often context- and task-specific, making them difficult to model analytically. LLMs give us the ability to delve into these nuances, while the agents help us construct a dynamic, end-to-end workflow. At the same time, we employ guardrails, such as analytical rule-based risk computation, to ensure that the agents operate within set boundaries. Throughout the decision-making process, we also place a strong emphasis on transparency and tracing.

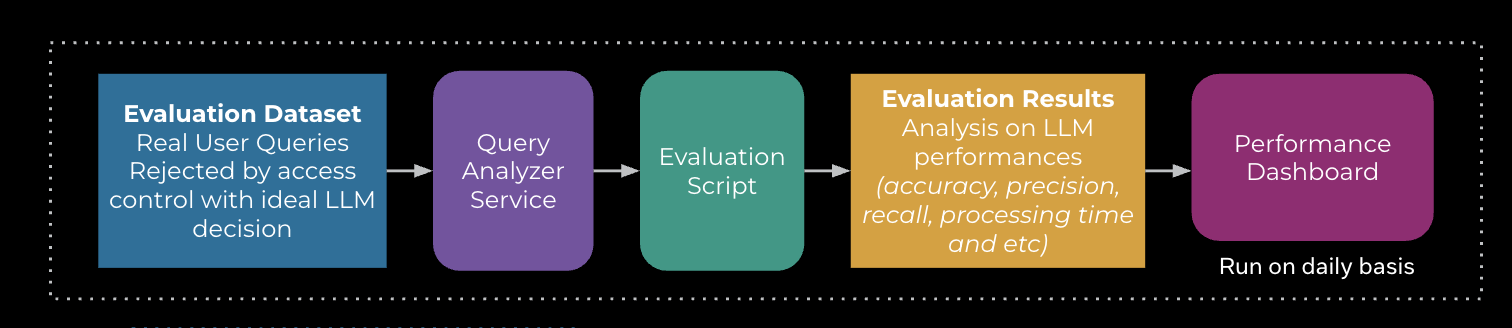

Below, Figure 12 shows the evaluation process. Evaluation is one of the most crucial steps in developing an agentic solution. To assess the system’s accuracy, recall, and other performance metrics, we curated an evaluation dataset using real requests. This involved compiling historical requests, collecting user activities and profile information, associating them with query runs, and then using this data for evaluation. We run the evaluation process daily to catch any potential regressions.

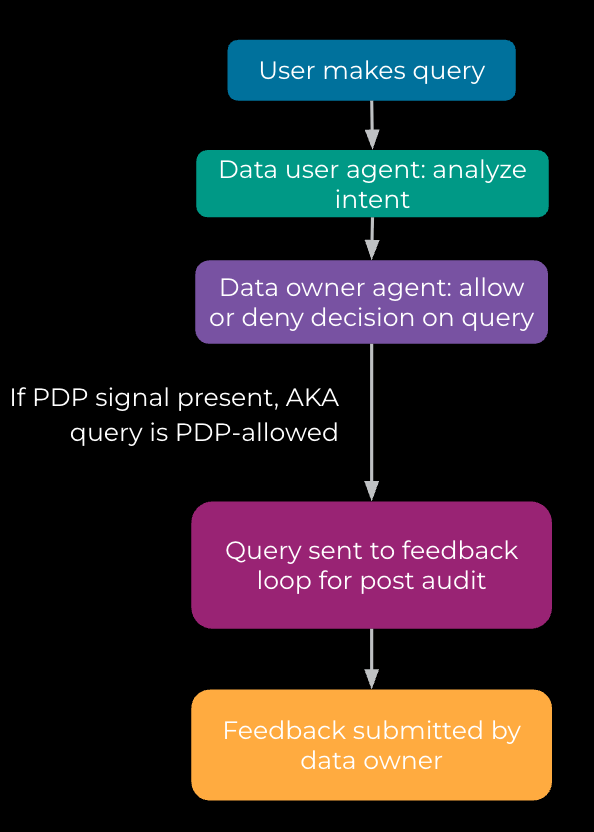

We’ve also developed a data flywheel for the process, as illustrated below in Figure 13. This means that data users’ queries, the agents’ processing traces, the context, and the final outputs are all securely stored for feedback and auditing purposes. Additionally, we’ve created a data tool for data owners, allowing them to view and review decisions and provide us with feedback. This feedback helps us update our evaluations and assess the overall process.

What’s ahead?

There’s still plenty of work ahead of us to become agent-ready. Here are just a few examples.

- First, agent collaboration. We’re seeing more and more scenarios where it’s not the users directly accessing data, but rather agents acting on their behalf. How can we support these use cases in the most efficient way?

- Second, our data warehouse and tools were originally built for employees or services, not agents. How do we continue evolving them to be effectively used by other agents?

- Lastly, evaluation and benchmarking are important, and we’ll need to keep developing these areas to ensure we stay on track.