Today, we are sharing details about Pysa, an open source static analysis tool we’ve built to detect and prevent security and privacy issues in Python code. Last year, we shared how we built Zoncolan, a static analysis tool that helps us analyze more than 100 million lines of Hack code and has helped engineers prevent thousands of potential security issues. That success inspired us to develop Pysa, which is an acronym for Python Static Analyzer.

Pysa is a security-focused tool built on top of our type checker for Python, Pyre. It’s used to look at code and analyze how data flows through it. Analyzing data flows is useful because many security and privacy issues can be modeled as data flowing into a place it shouldn’t.

Pysa helps us detect a wide range of issues. For example, we use it to check whether our Python code properly makes use of certain internal frameworks, which are designed to prevent access to, or disclosure of, user data based on technical privacy policies. Pysa also detects common web app security issues, like XSS and SQL injection. Like Zoncolan has done for Hack code, Pysa has helped us scale our application security efforts for Python, most notably the codebase that powers Instagram’s servers.

Pysa on Instagram

Our largest repository of Python code is the millions of lines that power Instagram’s servers. Automated analyzers like Pysa are an important tool for maintaining quality and security in this codebase. When we run Pysa on a developer’s proposed code change, the tool provides results in about an hour rather than the weeks or months it could take to review manually. These rapid results help us find and prevent an issue fast enough to keep it from being introduced into our codebase. The results go either directly to the developer or to security engineers, depending on the type of issue detected and the signal-to-noise ratio of our detections for that specific issue.

Open-sourcing Pysa

We’ve made Pysa open source, together with many of the definitions required to help it find security issues, so that others can use the tool for their own Python code. Because we use open source Python server frameworks such as Django and Tornado for our own products, Pysa can start finding security issues in projects using these frameworks from the first run. Using Pysa for frameworks we don’t already have coverage for is generally as simple as adding a few lines of configuration to tell Pysa where data enters the server.

We’ve used Pysa to detect and disclose security issues on open source Python projects, such as CVE-2019-19775. We’ve also worked with the Zulip open source project to incorporate Pysa into its codebase.

How Pysa works

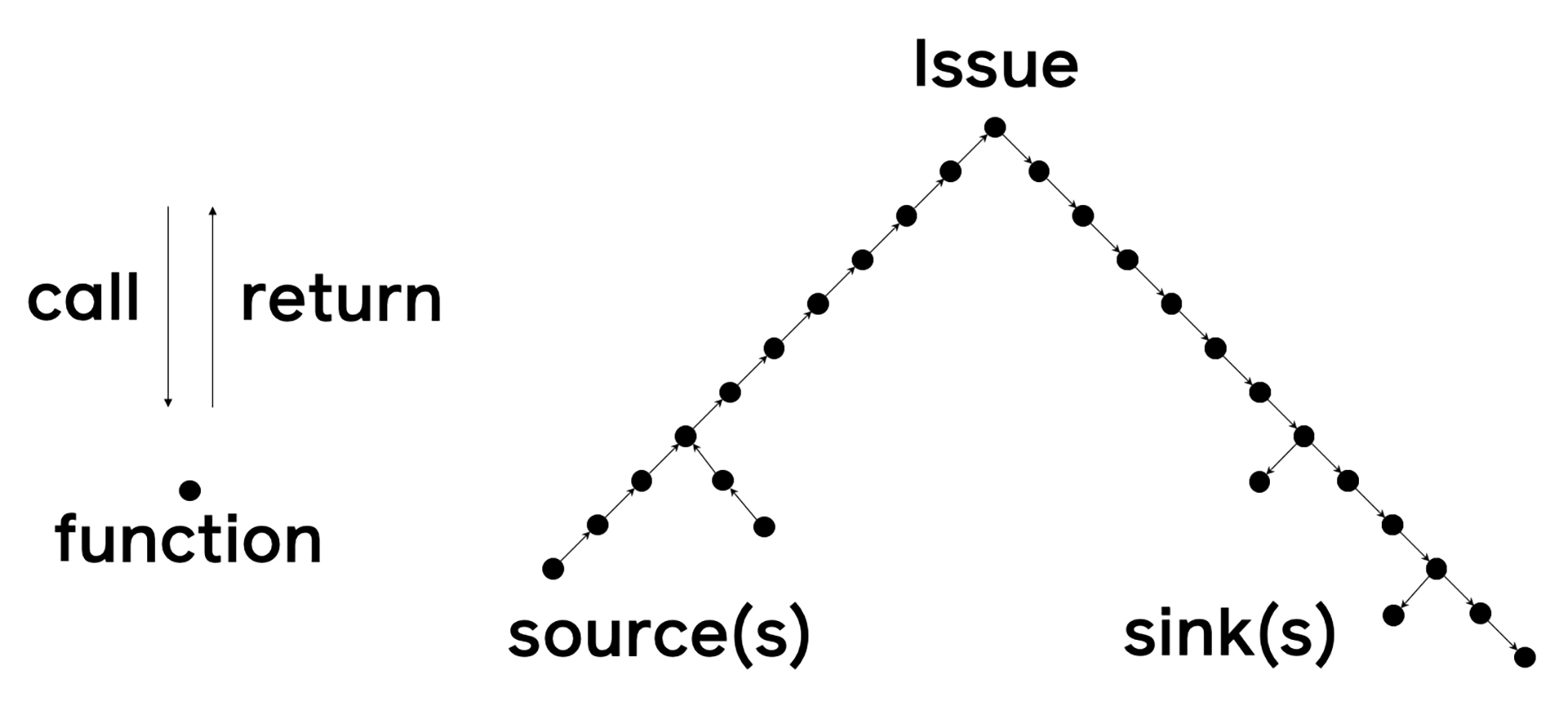

Pysa was developed with the lessons learned from Zoncolan in mind. It uses the same algorithms to perform static analysis and even shares some code with Zoncolan. Like Zoncolan, Pysa tracks flows of data through a program. The user defines sources (places where important data originates) as well as sinks (places where the data from the source shouldn’t end up). For security applications, the most common kinds of sources are places where user-controlled data enters the application, such as Django’s HttpRequest.GET dictionary. Sinks tend to be much more varied but can include APIs that execute code, such as eval, or APIs that access the file system, such as os.open. Pysa performs iterative rounds of analysis to build summaries to determine which functions return data from a source and which functions have parameters that eventually reach a sink. If Pysa finds that a source eventually connects to a sink, it reports an issue. Visualizing this process creates a tree, with the issue at the apex and sources and sinks at the leaves:

To be able to perform interprocedural analysis — following flows of data across function calls — we needed to be able to map function invocations to their implementations. To do this, we needed to use all available information in the code, including optional static types (when present). We use our static type checker, called Pyre, to understand this information. While Pysa relies heavily on Pyre and the two share a repository, it’s important to note that they are separate products with separate applications.

False positives and negatives

Our security engineers are the primary users of Pysa within Facebook. Like any engineers that use automated tools for detection, we’ve had to decide how to deal with false positives and false negatives.

- False positives occur when a tool reports that a security issue is present where none actually exists.

- False negatives occur when a tool fails to detect and report when a real security issue is present.

Because of the importance of catching security issues, we built Pysa to avoid false negatives and catch as many issues as possible. Reducing false negatives, however, may require trade-offs that increase false positives. Too many false positives could in turn cause alert fatigue and risk real issues being missed in the noise.

We built two kinds of functionality into Pysa to give users the tools to remove false positives: sanitizers and features.

- Sanitizers are a blunt tool: During the analysis process, they tell Pysa to completely stop following a data flow after it passes through a function or attribute. They allow users to encode their domain-specific knowledge about transformations that will always render data benign from a security or privacy perspective.

- Features allow a more nuanced approach: Features are little pieces of metadata that Pysa can attach to flows of data as they are being tracked throughout the code. Unlike sanitizers, adding features doesn’t remove any issues from Pysa’s results.

Features and other metadata can be used to filter the results after analysis is done. Filters are usually written for a specific source-sink pair to ignore issues where data was rendered benign for a specific kind of sink, but not for all kinds of sinks.

Example

To understand where Pysa is most useful, imagine the following code was used to load a user’s profile:

# views/user.py

async def get_profile(request: HttpRequest) -> HttpResponse:

profile = load_profile(request.GET['user_id'])

...

# controller/user.py

async def load_profile(user_id: str):

user = load_user(user_id) # Loads a user safely; no SQL injection

pictures = load_pictures(user.id)

...

# model/media.py

async def load_pictures(user_id: str):

query = f"""

SELECT *

FROM pictures

WHERE user_id = {user_id}

"""

result = run_query(query)

...

# model/shared.py

async def run_query(query: str):

connection = create_sql_connection()

result = await connection.execute(query)

...

As it stands, the potential SQL injection in load_pictures is not exploitable, because that function will only ever receive the valid user_id that resulted from calling load_user in the load_profile function. When configured correctly, Pysa would probably not report an issue here.

Now, imagine that an enterprising engineer working on the controller layer of the application realized that fetching the user and picture data concurrently returns results faster:

# controller/user.py

async def load_profile(user_id: str):

user, pictures = await asyncio.gather(

load_user(user_id),

load_pictures(user_id) # no longer 'user.id'!

)

...

This change may look innocuous but actually ends up connecting the user-controlled user_id string directly to the SQL injection issue in load_pictures. In a large application with many layers between the entry point and database queries, this engineer might never realize that the data is fully user controlled, or that a SQL injection issue lurks in one of the functions called. This, however, is exactly what Pysa was designed to know. If an engineer proposed a change like this on Instagram, Pysa could detect that there was data flowing all the way from user-controlled input to a SQL query and flag the issue.

Limitations

Fundamentally, there is no way to build a perfect static analyzer. Pysa has limitations based on its choice to address security issues related to data flow, together with design decisions that trade off performance for precision and accuracy. Python, as a dynamic language, has unique features that underlie some of those design decisions.

Problem space

Pysa is built to discover only data flow–related security issues, but not all security or privacy issues can be modeled as flows of data. Consider this example code:

def admin_operation(request: HttpRequest):

if not user_is_admin():

return Http404

delete_user(request.GET["user_to_delete"])

Pysa is not the right tool to ensure that an authorization check, such as user_is_admin, was triggered before a privileged operation, such as delete_user. Pysa could detect data from request.GET flowing into delete_user, but that data doesn’t ever pass through the user_is_admin check. This code could be rewritten to make the problem modelable by Pysa, or to make it safer by embedding the permission check in the administrative delete_user operation, but it serves to show that Pysa can’t detect all forms of security issues.

Resource constraints

We’ve had to make design decisions so that Pysa can finish its analysis before developers’ proposed changes land. For example, when Pysa is tracking data flows into too many attributes of an object, it sometimes has to simplify and treat the whole object as containing that data, which could lead to false positives.

Development time is also a resource constraint, which has caused us to make trade-offs on which Python features we support. For example, Pysa doesn’t yet include decorators in the call graph when invoking functions, and thus might miss issues that occur within decorators.

Python as a dynamic language

Some of the features that make Python such a flexible language also make it harder to statically analyze. For example, it’s difficult to track flows of data through method calls without type information. In the following code, it’s impossible to tell which implementation of fly is called:

class Bird:

def fly(self): ...

class Airplane:

def fly(self): ...

def take_off(x):

x.fly() # Which function does this call?This isn’t to say Pysa can’t run on untyped code; it can and has found security issues in fully untyped projects, but a little effort to add coverage for important types is needed.

The dynamism of Python also places another limitation on Pysa. Consider the following code:

def secret_eval(request: HttpRequest):

os = importlib.import_module("os")

# Pysa won't know what 'os' is, and thus won't

# catch this remote code execution issue

os.system(request.GET["command"])

There is a code execution vulnerability in this code, but Pysa wouldn’t catch it because the os module is dynamically imported and Pysa doesn’t realize that that’s what the local os variable represents. Python lets you dynamically import virtually any code at any point. Python also lets you change what a function call on virtually any object will do. While Pysa could be updated to parse the “os” string in the above example and detect the issue, the dynamism of Python means there are endless pathological examples of flows of data that Pysa cannot detect.

Results

Pysa helps security engineers both detect existing issues in a codebase and prevent new ones from being introduced via proposed code changes. In the first half of 2020, Pysa detected 44 percent of the issues that our engineers found in the Instagram server codebase.

Across all vulnerability types, Pysa detected 330 unique issues in proposed code changes which we categorized by severity. In total, 49 (15 percent) were significant issues, and 131 (40 percent) of the remaining results were real but had mitigating circumstances that made them less severe. Even with Pysa’s bias to avoid false negatives and our willingness to accept a good number of false positives, we still managed to cap false positives at 150 (45 percent) of the reported issues.

We regularly review issues reported through other avenues, such as our bug bounty program, to ensure that we correct any false negatives. Each detection for a vulnerability type is tunable. Through continuous refinement, security engineers have been able to move the more refined types to report 100 percent valid issues.

Overall, we are happy with the trade-offs we’ve made with Pysa to help security engineers scale, but there is always room to improve. We built Pysa for continuous improvement, thanks to a close collaboration between security engineers and software engineers. This has allowed us to iterate quickly and build a tool that suits our needs in a way that we could never have done with an off-the-shelf solution. This collaboration has already resulted in additions and refinements to how Pysa works. For example, it has helped us improve how we browse traces for issues, which makes it easier to identify when an issue is a false positive.

Pysa is following in the footsteps of Zoncolan by allowing us to automate the detection of security issues in our Python code. It has enabled us to detect security issues in our own code and in open source projects. Pysa is free, open source, and available for anyone to start analyzing their Python code by following along with the documentation and tutorial. We would love for you to give it a try!

Building Pysa and putting it to use has been a massive undertaking. Thank you to all these people for their contributions to the effort: Maxime Arthaud, Apurv Bhargava, Jia Chen, Manuel Fahndrich, Lorenzo Fontana, Dominik Gabi, Nolan Alexander Jimenez, Zack Landau, Mark Mendoza, Eray Mitrani, Ibrahim Mohamed, Maggie Moss, Radu Nesiu, Nicholas O’Brien, Edward Qiu, Pradeep Kumar Srinivasan, and Shannon Zhu.