Facebook uses machine learning and ranking models to deliver the best experiences across many different parts of the app, such as which notifications to send, which stories you see in News Feed, or which recommendations you get for Pages you might want to follow. To surface the most relevant content, it’s important to have high-quality machine learning models. We look at a number of real-time signals to determine optimal ranking; for example, in the notifications filtering use case, we look at whether someone has already clicked on similar notifications or how many likes the story corresponding to a notification has gotten. Because we perform this every time a new notification is generated, we want to return the decision for sending notifications as quickly as possible.

More complex models can help improve the precision of our predictions and show more relevant content, but the trade-off is that they require more CPU cycles and can take longer to return results. Given these constraints, we can’t always evaluate all possible candidates. However, by improving the efficiency of the model, we can evaluate more inventory in the same time frame and with the same computing resources.

In this post, we compare different implementations of a type of predictive model called a gradient-boosted decision tree (GBDT) and describe multiple improvements in C++ that resulted in more efficient evaluations.

Decision tree models

Decision trees are commonly used as a predictive model, mapping observations about an item to conclusions about the item’s target value. It is one of the most common predictive modeling approaches used in machine learning, data analysis, and statistics due to its non-linearity and fast evaluation. In these tree structures, leaves represent class labels and branches represent conjunctions of features that lead to those class labels.

Decision trees are very powerful, but a small change in the training data can produce a big change in the tree. This is remedied by the use of a technique called gradient boosting. Namely, the training examples that were misclassified have their weights boosted, and a new tree is formed. This procedure is then repeated consecutively for the new trees. The final score is taken as a weighted sum of the scores of the individual leaves from all trees.

Models are normally updated infrequently, and training complex models can take hours. At Facebook’s scale, however, we want to update the models more often and run them on the order of milliseconds. Many backend services at Facebook are written in C++, so we leveraged some of the properties of this language and made improvements that resulted in a more efficient model that takes fewer CPU cycles to evaluate.

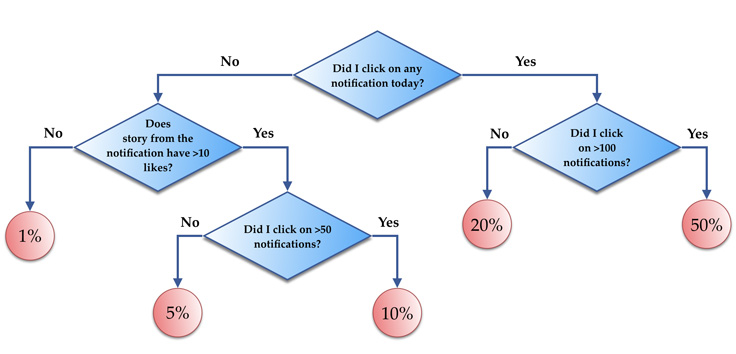

In the next figure we have a simple decision tree with the following features:

- the number of clicks on notifications from person A today (feature F[0])

- the number of likes on the story corresponding to the notification (feature F[1])

- the total number of notification clicks from person A (feature F[2])

At different nodes, we check the values of the above features and traverse the tree to get the probability of clicking on a notification.

Flat tree implementation

The naive implementation of the decision tree model is a simple binary tree with pointers. However, this is not very efficient due to the fact that the nodes do not need to be stored consecutively in the memory.

On the other hand, decision trees are usually full binary trees (a binary tree in which each node has exactly zero or two children) and can be stored compactly using vectors. No space is required for the pointer; instead, the parent and children of each node can be found by arithmetic on array indices. We will use this implementation for comparison in the experimentation section.

Compiled tree implementation

Each binary tree can be represented as a complex ternary expression, which can be compiled and linked to a dynamic library (DLL) that can be directly used in the service. Note that we can add or update the decision tree model in real time without restarting the service.

We can also take advantage of LIKELY/UNLIKELY annotations in C++. They are directions for the compiler to emit instructions that will cause branch prediction to favor the “likely” side of a jump instruction. If the prediction is correct, it means that the jump instruction will take zero CPU cycles. We can compute branch predictions based on the real samples from the ranking in batches or from the offline analysis, as the distributions from training and evaluation sets should not change much.

The following code represents an implementation of the above simiple decision tree:

int tree(double* F) {

return LIKELY(F[0] < 1)

? (UNLIKELY(F[1] > 10) ? (F[2] > 50 ? 0.1 : 0.05) : 0.01)

: (F[2] > 100 ? 0.5 : 0.2);

}

Model range evaluation

In a typical ranking setup, we need to evaluate the same trained model on multiple instances of feature vectors. For example, we need to rank ~1,000 different potential candidates for a given person, and pick only the most relevant ones.

One approach is to iterate through all candidates and rank them one by one. Typically, the model and all candidates cannot fit together into the CPU instruction cache. Motivated by the boosted training, we can actually split the model into ranges of trees (the first N trees, then the next N trees, and so on), so that each range will be small enough to fit the cache memory. Then we can flip the evaluation order: Instead of evaluating all trees on a sample, we will evaluate all samples on each range. This way we can fit the whole tree set in the CPU cache together with all feature vectors, and in the next iteration just replace the tree set. This reduces the number of cache misses and uses block reads/writes instead of RAM.

Furthermore, we often have multiple models that we need to evaluate on the same feature vectors; for example, the probability of the user clicking, liking, or commenting on the notification story. This helps keep all feature vectors in the CPU cache and evaluating models one by one.

Another trade-off that we can make is to rank all candidates for the first N trees and then, due to the nature of boosted algorithms, discard the lowest-ranked candidates. This can improve the latency, but it comes with a slight drop in accuracy.

Common features

Sometimes features are common across all feature vectors. In the above example for a certain person, we need to rank all candidate notifications. The feature vectors [F[0], F[1], F[2]] described above can be something like this:

[0, 2, 100]

[0, 0, 100]

[0, 1, 100]

[0, 1, 100]

It’s easily noticeable that the features F[0] and F[2] are the same for candidates. We can significantly reduce the decision tree size by just focusing on the value F[1], and thus improve the evaluation time.

Categorical features

Most ML algorithms use binary trees, and this can be extended to k-ary trees. On the other hand, some of the features are not actually comparable and are called categorical features. For example, if country is a feature, one cannot say whether the value is less than or equal to “US” (or a corresponding enum value). If the tree is deep enough, this comparison can be achieved using multiple levels, but here we implemented the possibility for checking whether the current feature belongs to a set of values.

The learning method is not changed much — we still try to find the best subset to split on, and the evaluation is very fast. Based on the size of the set, we use the in_set C++ implementation or just concatenate if conditions. This reduces the model size and helps in convergence as well.

Computational results

We trained a boosted decision tree model for predicting the probability of clicking a notification using 256 trees, where each of the trees contains 32 leaves. Next, we compared the CPU usage for feature vector evaluations, where each batch was ranking 1,000 candidates on average. The batch size value N was tuned to be optimal based on the machine L1/L2 cache sizes. We saw the following performance improvements over the flat tree implementation:

- Plain compiled model: 2x improvement.

- Compiled model with annotations: 2.5x improvement.

- Compiled model with annotations, ranges and common/categorical features: 5x improvement.

The performance improvements were similar for different algorithm parameters (128 or 512 trees, 16 or 64 leaves).

Conclusion

These improvements in CPU usage and resulting speedups allowed us to increase the number of examples we rank or increase the model size using the same amount of resources. This approach has been applied to several ranking models at Facebook, including notifications filtering, feed ranking, and suggestions for people and Pages to follow. Our machine learning platforms are constantly evolving; more precise models combined with more efficient model evaluations will allow us to continually improve our ranking systems to serve the best personalized experiences for billions of people.